Overseas chinese girl dating mainland chinese guy - about

Can: Overseas chinese girl dating mainland chinese guy

| What to know about dating science guys | Dating apps that filter on language spoken |

| 100 free dating sites in netherland | Free dating sites transgender |

| Completely free dating sites for married | Tall guy dating |

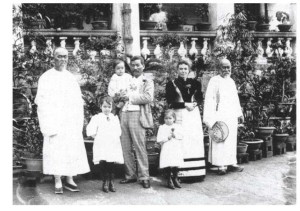

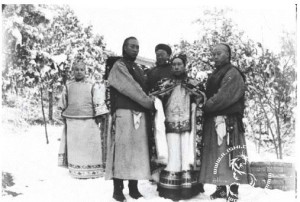

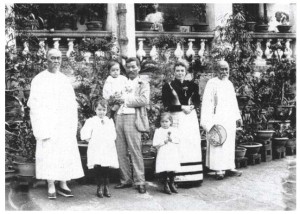

Australian wife Margaret and her Chinese husband Quong Tart and their three eldest children, 1894.

Source: Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists

1.1 Brief Introduction

It is now becoming more and more common to see Chinese-Western intercultural couples in China and other countries. In the era of the global village, intercultural marriage between different races and nationalities is frequent. It brings happiness, but also sorrow, as there are both understandings and misunderstandings, as well as conflicts and integrations. With the reform of China and the continuous development, and improvement of China’s reputation internationally, many aspects of intercultural marriage have changed from ancient to contemporary times in China. Although marriage is a very private affair for the individuals who participate in it, it also reflects and connects with many complex factors such as economic development, culture differences, political backgrounds and transition of traditions, in both China and the Western world. As a result, an ordinary marriage between a Chinese person and a Westerner is actually an episode in a sociological grand narrative.

This paper reviews the history of Chinese-Western marriage in modern China from 1840 to 1949, and it reveals the history of the earliest Chinese marriages to Westerners at the beginning of China’s opening up. More Chinese men married Western wives at first, while later unions between Chinese wives and Western husbands outnumbered these. Four types of CWIMs in modern China were studied. Both Western and Chinese governments’ policies and attitudes towards Chinese-Western marriages in this period were also studied. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, from 1949 to 1978, for reasons of ideology, China was isolated from Western countries, but it still kept diplomatic relations with Socialist Countries, such as the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries. Consequently, more Chinese citizens married citizens of ex-Soviet and Eastern European Socialist Countries. Chinese people who married foreigners were usually either overseasstudents, or embassy and consulate or foreign trade staff. Since the economic reformation in the 1980s, China broke the blockade of Western countries, and also adjusted its own policies to open the country. Since then, international marriages have been increasing. Finally, this chapter discusses the economic, political and cultural contexts of intercultural marriage between Chinese and Westerners in the contemporary era.

1.2 Chinese-Western Intermarriage in Modern China: 1840–1949

In ancient China, there are three special forms of intercultural/interracial marriages. First, people living in a country subjected to war often married members of the winning side. For instance, in the Western Han Dynasty, Su Wu was detained by Xiongnu for nineteen years, and married and had children with the Xiongnu people. In the meantime, his friend Li Ling also married the daughter of Xiongnu’s King[i]; In the Eastern Han Dynasty, Cai Wenji was captured by Xiongnu and married Zuo Xian Wang and they had two children.[ii] The second example is the He Qin (allied marriage) between royal families in need of certain political or diplomatic relationships. The (He Qin) allied marriage is very typical and representative within the Han and Tang Dynasties. The third example is the intercultural/interracial marriages between residents of border areas and those in big cities. As to the former two ways of intercultural/ interracial marriage in Chinese history, the first one happened much more in relation to the common people plundered by the victorious nation, while the second one was an outer form of political alliance. The direct reason for the political allied marriage was to eliminate foreign invasion and keep peace. In that case, when the second form went smoothly, the first form inevitably ceased, however, when the first form increased, the second form failed due to the war.

In modern China, intercultural marriages are very different from the ancient forms. The Industrial Revolution and developments in technology have accelerated people’s lifestyles and broadened their visions. The industrial age broke through the restrictions on human living standards imposed by the Agricultural age, and it has given rise to a transformation in human social life, modes of thinking, behaviour patterns and many other aspects. All these changes have had profound effects on means of human communication, association and contact. With the increase in productive powers of the community and the development of technologies, new systems and orders have been transformed and reconstructed in many aspects of the human world, such as in the fields of economy, trade, markets, politics, society, and even conventional social behaviour. New political systems were widely established in many countries in the world at the time. Theories of natural rights, the social contract and the people’s sovereignty had been developing in Capitalist countries, thus free competition and free trade were the main themes of the modern era. The He Qin (allied marriages) in both ancient China and ancient Europe lost the basis of their existence. At the same time, frequent wars, increased trade, international business and more developed transportation systems had all been involving more and more countries and people, leading to people being able to associate with others with greater convenience and freedom than ever before. In comparison to previous times in history, great changes had also taken place in relation to international marriages in the world generally as well as in modern China.

1.2.1 Four Types of Chinese-Western Intermarriage in Modern China

Established by Manchu, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) reigned over the greatest territories of any of the Chinese Empires in history. It included numerous races, all related to Chinese civilisations from ancient times, and it made China a unitary multinational state with the largest territory for the first time[iii]. In terms of internal affairs, the Qing Dynasty regime was relatively enlightened and managed state affairs in a prudent way. Although ethnic discrimination and oppression did exist, intermarriage between different races was not restricted or interfered with. The only exception was the prohibition on marriage between Manchu and Han Chinese. For more than 300 years of the Qing Dynasty, intermarriage between different races, other than Han and Manchu, within China was very common. The royal family of the Qing dynasty maintained frequent He Qin marriages with the upper class of Mongolia, and they sent their princesses and aristocratic ladies to marry the Mongolian kings and dukes[iv]. For example, Qing Taizu had married his third daughter to Borjigin Suomuruoling and Qing Tai Zong married his eldest daughter, Gulun princess to Borjigin Bandi. In the meantime, the sons of the royal family of Qing had taken the daughters of Mongolian kings and dukes as empresses and imperial concubines[v].

Nevertheless, apart from intermarriage with people at border regions and between adjacent neighbouring countries, intermarriage between Chinese and more distant westerners was rare before 1840. The reason was that the essential characteristics of foreign policy of the Qing Dynasty were concerned with closing China away from the outside world, and maintaining things as they were. In this way it refused such progress. The Qing Government closed the country in 1716 keeping only four trading ports, and a stricter code was implemented in 1757 leaving only one trading port, Guangzhou.[vi]

This was determined by the basic conditions governing social, political, economic and cultural status of that time. In the middle period of the Qing Dynasty, a policy of trade restriction was implemented; only one port in Guangzhou was retained for external trade on the sea, and Kyakhta was kept for external trade with foreign countries on land. Foreign merchants were only permitted to contact business organisations designated by the Qing government for trade matters. The Qing government also restricted the activities of foreign merchants and the quantity of import and export goods [vii]. In addition, before the middle 19th century, Europeans were not permitted to travel in China freely. By closing China from the outside world, imposing a policy of restricting trade and foreigners from entering the country China lost opportunities for external trade, and from the perspective of transnational marriage, it broke off economic and cultural communication between China and foreign countries and increased the distance between China and the rest of the world, which resulted in the limitation of Chinese people’s foresight[viii], and provided no opportunities for marriage with Westerners.

In the late Qing Dynasty (1840-1912), the Opium War opened the doors of China. China’s defeat in the Opium War and the conclusion of the Treaty of Nanking had enormous consequences, as from then on China had lost its independence leading to significant changes within its society[ix]. The War was the birth of a Semi-Colonial and Semi-Feudal Society, and China was afterwards gradually reduced to a semicolonial and semi-feudal society. The word “Youli (Travel)” first appeared in the official documents of the Qing Dynasty after the Tianjin Treaty was signed between the Qing government and Britain in 1858. As regulated by Article 9 of this Treaty, British people were allowed to travel to and trade at various places inland with certain permits[x]. Particularly worthy of note was that, during the second Opium War, Britain, France and the USA all signed the Tianjin Treaty with the Qing government successively, but only Britain defined the concept of “Travel (You Li)” of Westerners in the Treaty with the Qing government. In this way it can be observed that the Tianjin Treaty between Britain and the Qing government started European travel within inland China[xi]. Along with more and more Westerners coming into China, the policies of the Qing government became more open. A great many foreigners poured in leading to a gradual increase in intermarriage between Chinese and foreigners.

In December of 1850 the Taiping Rebellion, led by Hong Xiuquan, happened in China lasting from 1850 t0 1864, when the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was instated.[xii] The Taiping Rebels considered themselves Christian and believed in God and Jesus, therefore they considered Western countries their “brothers” and “friends”, and even fantasised that the Western powers could help them overthrow the Qing Government in the name of God[xiii]. With this diplomatic aim, Taiping Rebels had been seeking opportunities to associate with Western powers actively from the beginning. In 1853, Yang Xiuqing, Dong King of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, said in his imperial mandated breve to British Envoy, Sir George Bonham: “You British people come to China from ten thousands miles away to pay allegiance to our Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, not only the officers and soldiers of our Celestial Empire will welcome you warmly, but also God and Jesus will also praise and reward your loyalty. Notice is hereby given that you British chieftain can bring your nationals to enter and leave China freely. You are free to come and go at your pleasure, and you can suit your own convenience to do your business and trade as usual whether you assist our heavenly soldiers to exterminate the evil enemies (Qing Government) or not. We ardently anticipate that the British can help and be dutiful to our Heavenly King together with us, to build up our establishment and great deeds in order to repay the great obligations of God.[xiv]”

Later, Western powers helped the Qing government to suppress the Taiping army, but the leaders of the Taiping Rebels still believed that “Westerners and we both believe in God, and our religion is the same, therefore they are not hypocritical and don’t have bad intentions. We hold the same religion, and our friendship with Westerners is as good as with family members.[xv]” Against this background, the areas of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom were opened to Westerners, and many Westerners came to China leading to greater possibilities of Chinese-Western intermarriages. In addition, one of the most remarkable transformations in Taiping Rebel areas occurred in its gender policies and marriage system. Because of the Christian belief that people are “all God’s children ”[xvi], the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom operated a series of policies to achieve equality between men and women. Firstly, women were permitted to take the same exams as men to act as officials in government, and “women officials” were established in Taiping areas[xvii]. This surely changed the traditional role of Chinese women who had hitherto no political status and represented great progress in gender relations in feudal China. Secondly, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom opposed and abolished women’s footbinding and living in widowhood[xviii]. Mercenary marriage and concubinage were also prohibited, and monogamy was advocated as normal practice[xix]. Marriages were required to be registered in civil departments, through which couples could acquire their marriage certificate. The earliest modern marriage certificate, the “He Hui” certificate appeared for its first time in modern Chinese history in Taiping areas[xx]. All of these policies and reforms that took place in Taiping areas paved the way for greater opportunities for foreigners to enter China, increased association between Chinese people and foreigners, and ultimately intercultural marriages.

The Second Opium War broke out in 1856 and lasted until 1860 when China was defeated again[xxi]. The Qing Government began to recognise its weaknesses and the strengths of Western countries, and consequently began to send Chinese students to study in the USA and Europe in 1871, during which many students married foreign wives. In the meantime, the Qing government began to establish diplomatic relations with more and more foreign countries, and some of the Chinese diplomats involved also married foreign wives in foreign countries. Since its initial opening, China has been compelled to open up further to the greater world. This has increased business and trade, foreign affairs, overseas study and even “Selling Piglets (labour output)”[xxii], leading to transnational marriages becoming more common and the corresponding legal documents required being established successively. The earliest legal documents were Regulations upon Marriages between Chinese and German People in 1888, and Relevant Notes between China and Italy in 1889[xxiii], which stated clearly that “Within the territory of China, if Chinese women are going to marry foreigners, the foreign men must report to local officials to obtain legal permission. And the Chinese women marrying foreigners should be supervised by their husbands[xxiv]. If the Chinese men are going to marry foreigners, the foreign women should also follow the example of being supervised by their husbands.”;If there was involvement in legal cases before or after marriage, and if the female suspect hoping to escape the law by marrying into foreign countries was found out, they would be transferred to be judged by Chinese local officials[xxv]. Besides male superiority to females both in China and in Western countries, these treaties were basically equal.

In 1894, the first war between Meiji Japan and Qing China in modern times was fought. The cause of this war was that both China and Japan contested the control of Korea[xxvi]. Japan and China both increased political instability in Korea by intervening militarily. As the suzerain of Korea, China came at the invitation of the Korean king with the intention of retaining its traditional suzerian-triburary relationship, while Japan came bent on war with the intention of preventing the Russian annexation of the Korean Peninsula[xxvii], and more importantly, destroying the traditional Eastern Asian Tributary System[xxviii] which removed China from the centre and replaced it with the Japan-Centric East Asia International System, in order to achieve its further plan of invading China and expanding in Asia, which accorded with the Japan Meiji Government’s consistent schema[xxix]. The war ended with the defeat of China’s Qing in April of 1895. The war intensified the semifeudal and semicolonial nature of society in China, and the humiliating defeat of China sparked an unprecedented public outcry leading to the Wu Xu Reform movement in 1895 after the Qing Government signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki. A thousand or more candidates from all eighteen provinces including Taiwan who had assembled in Beijing for the Imperial Examination, captained by Kang Youwei[xxx], signed a strongly-worded petition opposing the ceding of Taiwan. This was called the “Gong Che Shang Shu” affair within Wu Xu period of reform (1895-1898)[xxxi].

The main aim of Wu Xu was to spark constitutional reform and modernisation, strengthen China and protect its people, and it was also very much concerned with women’s and marriage issues because marriage and the family was the foundation of the Chinese feudal society which badly needed reform. The new regime firstly emancipated Chinese women to a great extent in modern China. New and anti-traditional marriage issues were widely discussed publicly in newspapers and periodicals in the Wu Xu reform period for the first time[xxxii]. Reformists introduced the “new images” of the Western woman in contrast to the “old” images of the Chinese woman, and they criticised and argued against the Chinese feudal code of ethics and customs that affected marriages in a comprehensive and profound way, such as Baoban Hunyin (arranged marriage), Cong Yi Er Zhong (be faithful to one’s husband to the very end), Nan Nv Da Fang (the chastity value) and Rigorous Preventions between Males and Females and concubinage. They also condemned the traditional gender order which caused Chinese women and young people to be physically and emotionally abused when they encountered marriage choices. Cases demonstrating the freedoms existing in marriage in Western countries and Japan were widely reported[xxxiii]. During the Wuxu Period, the member of famous reform group, Tang Caichang, published his revolutionary “Tong Zhong Shuo (Theories of Miscegenation)”, in which they advocated intermarriage between Chinese and Westerners and the implementation of intermarriage to improve the Chinese race. This book presented a rare theory for China at the end of the 18th Century, and it was the first time in China that interracial and intercultural marriages were discussed against a wider context addressing such a momentous topic as the future of the Chinese nation. This could be seen as the first time that that the Chinese systematically thought and studied interracial and intercultural marriages between Chinese and Westerners.

The Wu Xu movement produced a more acceptable condition for intercultural marriages at that time. Another contribution of Wu Xu reformists was the development of women’s education, and it was an initial and important step for women’s emancipation. Women’s education was strongly promoted in this era; many women colleges were established, and women’s legal right to have the same education as men was also gradually but effectively protected in the legislation of that time. The old feudal concepts discriminating against women, such as “Nvzi Wu Cai Bian Shi De (Innocence is the virtue for women)” and “San Cong Si De (the three obediences and the four virtues)” were gradually eroded, which paved the way for women’s education[xxxiv]. (Although Ningbo Zhuduqiao Women College, the first women college in China, was established in 1844 by Miss M.Aldersey, and after that some other women colleges were established in China, they were all missionary schools founded by Westerners. Only since the WuXu period, has the women’s college been properly established by the Chinese).[xxxv] More importantly, Chinese women also acquired the right to study abroad equal to Chinese men in the WuXu period. Chinese women’s education abroad was a key process that led to Chinese women challenging their feudal families and traditional society, and it was an epoch-making event in modern China. It had an extraordinary meaning as it implied that Chinese women began to escape from the feudal family’s dominion and to be free from the oppression of patriarchy, with their subordinate position being changed gradually. Along with Chinese male students, Chinese women students began to pursue their loves freely and some of them married foreigners.

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown, and the Republic of China was established. Since then, the social vogue has been more open and enlightened. The old marriage system was shaken and gradually eroded and monogamy was widely advocated and accepted. Freedom in marriage, divorce and remarriage caused strong and deep repercussions in Chinese society[xxxvi]. “Independent marital choice” and “Freedom in choosing spouses” were the main themes of this period. The new ideas around marriage incited young men and women to resist the feudal code of ethics[xxxvii], what was more, living together in a sexual relationship when not legally married became fashionable after the Xinhai Revolution.[xxxviii]

The May 4th Movement in 1919 was the next landmark in modern Chinese history, and it also signalled a new epoch in Chinese women’s emancipation.[xxxix]It could be considered as the watershed between new and old in modern China. As a major issue relating to happiness and freedom of the individual, marriage and marriage culture attracted much attention once again in China at the time.[xl] The New Culture Movement along with the May 4th Movement created an upheaval in the old feudal order of human relationships, and brought the principle of liberation of the personality, and equal rights for Chinese people. Chinese disenchantment continually rebelled against the old forms of marriage. The momentum of marriage transformation in this period exceeded that in Wuxu period, Xinhai period and early years of the Republic of China, (ROC) and it formed the pinnacle of marriage reform in modern China.[xli]With the introduction of western cultures and philosophies into China, the concept of absolute marriage freedom became more deeply rooted among its people. “Singleness, marriage, divorce, remarriage, and cohabitation should be absolutely free.”[xlii] “Making match by parents’ order and on the matchmaker’s word” was discarded, divorce and remarriage rates increased, and the emphasis on the chastity value started to fade in this period.[xliii] The ideas of Feminism came to the fore. More people had further opportunities to go abroad, and the government of ROC did not restrict its people from going abroad and indeed sent more students, workers and business to foreign countries, in turn leading to more Chinese-Western intercultural marriages. In 1946, with the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War (CCW), a surge in mobility of the population occurred again, and many Chinese refugees fleed to Western countries opening another door for CWIM.

With the transformations brought about by the two Opium wars, the Taiping Rebels, the Wuxu Reform, the Xinhai Revolution and the May 4th Movement, CCW became more frequent in modern China, and Chinese society gradually entered a new stage. The feudal and traditional values and concepts of marriage and the family have undergone unprecedented changes, and the Western marriage system and concept have been accepted by more and more Chinese. This was an important transition and omen for the transformation from traditional to modern marriage.[xliv] This transition and transformation broke through the restraints of the Chinese feudal family, and played a vital role in promoting social culture, emancipating people from rigid formalism and increasing the number of intermarriages between Chinese and Westerners, which produced far-reaching effects on Chinese society.

There were three types of intercultural marriage between Chinese and foreigners in modern China. The first type was the most important one: overseas intercultural marriage between Chinese diplomatic envoys and Chinese students studying abroad. The second type was foreigners in China married to Chinese, including those intercultural marriages that happened in Zu Jie (foreign concessions), and the third type was of Chinese labourers who were sent to Western countries on a large scale from modern China. I will describe the three types one by one.

A. The first type of intercultural marriage between Chinese and foreigners in this period was the overseas marriage of Chinese diplomatic envoys and Chinese students who were studying abroad.

Between the Late Qing dynasty and the First World War, following several defeats in wars with Western countries, the Qing government tried to seek a way to save its regime, and sending students to study abroad formed a major component of its plan. Many Chinese students that went abroad to Europe and the USA married Western women. There is a long history of Chinese students studying in western countries, which can be dated back to as early as 1871. From the mid to late 19th century, especially from 1871 to 1875, the Qing government dispatched the first large scale group of Chinese students abroad to study in Western countries.[xlv] From 1872 to 1875, with the leadership of the “Westernisation group” including Zeng Guofan, Li Hongzhang and Rong Hong,, the Qing Government had successively sent four groups of 120 children to study in America. Among them, more than 50 entered Harvard, Yale, Columbia, MIT and other renowned universities.[xlvi] In their memorials to the throne, Li Hongzhang and Zeng Guofan said that sending children to study in America is “an initiative deed in China which has never happened before”.[xlvii] As it had never happened before, the Qing government adopted a very serious attitude towards it. Its plan was to select brilliant children from different provinces, 30 a year and 120 in four years, and then to send them in different groups to study abroad. After 15 years, they would return to China. At that time, they would be about 30 so they would be in the prime of their lives and could serve the country well.[xlviii]

Picture 1.1 Chinese educational mission students Source: http://www.360doc.com/Chinese educational mission students sent by Qing government before they went to America in Qing dynasty.

Those students dispatched abroad were mostly male. When they reached western countries, as the first batch of Chinese to make contact with western land at that time, which entailed a totally different culture, society, set of customs and conceptualisation for male and female compared to China they experienced an unprecedented ideological shock. Chinese students abroad were attracted by the liveliness and romance of the Western female. One of the first Chinese students studying abroad to marry a Western wife was Yung Wing, who studied in the USA, and married an American woman, Miss Kellogg, of Hartford, who died in 1886.[xlix] Yung Wing probably was the first Chinese to go to study in the USA during the Qing dynasty, and he obtained a degree from Yale University. Yung Wing was born at Nanping, Xiangshan County (currently Zhuhai City) in 1828. In 1854, after Yung Wing graduated from Yale College, he came back to China with a dream that, through Western education, China might be regenerated, and become enlightened and powerful. From then on, he devoted his life to a series of reforms in China.

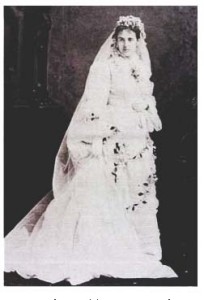

Picture 1.2 Mary Kellogg (18511886), wife of Dr. Yung Wing, at her wedding in 1875. Source: www.120chinesestudents.org

Another case was Kai Ho, who married a British woman. Kai Ho (1859–1914) was a Hong Kong Chinese barrister, physician and essayist in Colonial Hong Kong. He played a key role in the relationship between the Hong Kong Chinese community and the British colonial government. He is mostly remembered as one of the main supporters and teachers of student Sun Yat-sen. In 1887, he opened the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, which later became the basis from which the Hong Kong University was established in 1910. He married his British wife, Alice Walkden (1852–1884), in England in 1881 and returned to Hong Kong after his studies. Alice gave birth to a daughter, but died of typhoid fever in Hong Kong in 1884.[li] He later established Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital in her memory.[lii]

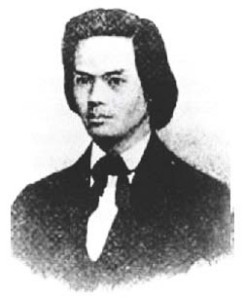

Picture 1.3 Dr. Yung Wing

Source: http://hongkongsfirst.blogspot.com

Picture 1.4 Alice Walkden: the English woman Ho Kai married in London in 1881

Source: http://hongkongsfirst.blogspot.com

As well as Chinese-Western intercultural marriages of Chinese students who studied overseas, in the late Qing Dynasty, many diplomats of the Qing government married Western wives. With the increasing contact with Western countries, the Qing government began to establish diplomatic relations with more and more foreign countries, leading to marriages between Chinese diplomats and foreign wives in foreign countries. One case was that of Chen Jitong, who was from Houguan (today’s Fuzhou), Fujian province. He studied at Fujian Chuanzheng Xuetang Fujian, (Ship-building and Navigation Academy) in his early years. In 1873, he became envoy to Europe for the first time, and two years later, took office in the France and Germany legation. He had been councillor of legation in Germany, France, Belgium and Denmark, and deputy envoy of legation in France, living in Paris and elsewhere in Europe for nearly 20 years.[liii] He was one of the first modern Chinese people to venture into the greater world. He was also the first appointed official of the Qing government to dare to bridge the gap between Chinese and foreigners and, in marrying a Westerner thereby attracting the disapproval of his countrymen, can be rated as another pioneer for intermarriage between Chinese and Westerners in modern China.

The Qing government lost the Sino-Japanese war in 1895. Like previous wars, this war intensified the semifeudal and semicolonial nature of society in China, and the humiliating defeat of China sparked an unprecedented public outcry leading to the Wu Xu Reform movement in 1895 after which the Qing Government signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Wu Xu reform concerned women and marriage issues very much because marriage and the family was the foundation of Chinese feudal society and needed to be transformed and reformed. With this new ethos, even the leader of Wu Xu reform, Kang Youwei, married two foreign wives, one American Chinese named He Zhanli[liv], the other Japanese named Ichioka Tsuruko.[lv] In addition, women began to have the same rights as men in terms of studying in college and studying abroad. The government began to send female students to foreign countries. The first group of women students (of 20 women) was sent to Japan in 1905[lvi], and the first group of women students was sent to the USA in 1907. Since then, more Chinese women students were sent to Europe, the USA and Japan.[lvii] Independent and free marriage was the first pursuit of Chinese women students who studied abroad. Many women were pressing for the end of arranged marriages, and those who had an arranged marital engagement required their families to dissolve it, those who had not arranged engagements in China naturally began to choose their love partners freely. It was very common for Chinese women to love another man in foreign countries, and some of them married local foreign men and settled there.[lviii]

During the Wu Xu Period, the reform group Tang Caichang published “Tong Zhong Shuo (Theories of Miscegenation)”, in which he advocated intermarriage between Chinese and Westerners and the implementation of intermarriage to improve the Chinese race. In the tenth argument listed in his article, he particularly quoted the transnational marriage of Chen Jitong, mentioned above, as an example to indicate that intermarriage with foreigners was not only expected but also possible to be implemented. He said in his article, “Feng Yi and Chen Jitong both married Western women. Those Western at that time did not despise intermarriage with people from a weak country as China, how can you people give aggressive expressions and indignation to intermarriage?”[lix] From these words we can see his admiration for the non-typical phenomenon of Chinese marrying Western women. In Zeng Pu’s famous novel Nie Hai Hua, the author also gave emphasis to describing the duel for possession of Chen Jitong between his French wife and English mistress. At the time when scholar-bureaucrats in the late Qing Dynasty were mostly ignorant of the outside world, and regarded Westerners as Deviants, Chen was bold and reckless to marry a Western female; moreover, when Chinese people were subjected to every kind of discrimination by European and American countries, and Chinese men still had the “pigtail”, there were still Western women who disregarded racial prejudice and adored Chen. (Note: in the plot about Chen Jitong in Nie Hai Hua by Zeng Pu, he was named “Chen Jidong” in the book). Chen Jitong married a French lady Miss Lai Mayi who later played a major role in Chinese women’s education, Wu Xu reform, the establishment of the first public schools for girls and the Chinese women’s newspaper[lx], and also had an English female doctor Shao Shuang who “admired his talent and followed him to China”, and gave birth to one son. This was similar to The Life of Chen Jitong (Chen Jitong Zhuan) by Shen Yuqing. In this book, it was also described that “he was skillful at shooting and riding horses. Where he was several meters from the horse, with one leap he can get on the horse; and when he used a gun to shoot a flying bird, he rarely missed it.”[lxi] The following photo shows Chen’s wife while she was staying with Empress Dowager CiXi.

Picture 1.6 Lai Mayi and Empress Dowager CiXi –

The left first is Chen’s wife

Like Chen Jitong, Yu Geng and his son, two diplomats, also took advantage of close connections. Yu Geng, whose wife was French, was generally known as a talent among the “Eight Banners”[lxii], and was an excellent tribute student during the Guangxu Period. First, he handed in a memorial to the throne against Ying Han, the governor of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. He held the position of Shaoqing in Taipusi, and then was sent on a diplomatic mission to Japan and France. He had two sons and two daughters, the elder son Xinlin, the younger son Xunlin, the elder daughter Delin, and the second one Ronglin. They all lived in Europe for many years with their parents, received a Western education, and had a good mastery of English and French. Yu Ronglin even learned Ballet in France.[lxiii] According to his youngerst child, Yu Geng had four children with his French wife Louisa Pierson:

My father, Lord Ku Keng, made a widower by the death of his first wife, married Louise Pierson of Boston, who gave him four children, two sons and two daughters, of whom I am the youngest. Princess Der Ling, my eldest sister…[lxiv]

Picture 1.7 The left third is Yu Geng’s French wife Louisa Pierson Source: http://www.ourjg.com/

During the two opium wars, China had been sending students to study overseas. After the Sino-Japan War, China continued to send students to Western countries, and more to Japan. More Chinese students also married foreigners. At the transition between Qing and the Republic of China, especially after the loss of the Sino-Japanese War in 1984, China began to learn from Japan. Many young men went there including Yang Erhe, Wu Dingchang, Jiang Baili, Fang Zong’ao, Yin Rugeng, Guo Muoruo, Tian Han, Tao Jingsun, Su Buqing and Lu Xun whose two bothers both married Japanese women. In 1904, the Qing government constituted the “Concise Statute of Studying in Western Countries”[lxv], and from then on, the number of Chinese students sent to Western countries increased. Chinese students who studied in western countries in the late Qing Dynasty had noticed the progressive development of Western women’s rights “in western countries, women were the same as men, they started studying when they were young, they learned painting and calligraphy, mathematics and astronomy, star images and geography, maps, classics of mountains and oceans, and got the essence of knowledge, even men in China can not match those females”.[lxvi] The New Record of Travelling around the Earth(Huanyou Diqiu Xin Lu) was the first book to record what he experienced as a participator in World Exposition, The author Li Gui on his journeys through Western countries saw the development of Western women’s rights for himself and expressed regret that women still could not study in the same as men in the China of the late Qing Dynasty, “According to western custom, female and male were of the same importance, the female can go to school the same as the male, so women can propose important suggestions and participate in important affairs”[lxvii], Mr. Zhong Shuhe praised this comment as a “declaration for equal women’s rights on a grand scale for the first time” in modern China.[lxviii]

After the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, the Republic of China was established but the Beiyang government kept the Qing’s policy of sending Chinse students to study in Western countries. With the funds of Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program[lxix] many students obtained opportunities to go abroad. The number of self-supporting and self-funding students also increased markedly. According to records, from 1913 to 1914, 1024 students were sent to Japan and 205 students were sent to Europe. In 1916, the number of students studying abroad on government funds was 1397. In 1917, 1170 students were sent to America, among them 200 students obtained government funds, 600 students were self-funded, and 370 students relied on the funds of Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program More intercultural marriages occurred.[lxx] After the May 4th Movement in 1919, the program of Work-for-Study in France became popular. From 1916 to 1917, more than 1600 students went to France for the Work-for-Study program. Many of the most important torchbearers for the People’s Republic of China went to France in this period, such as Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, Wang Ruofei, Chen Yi, Wu Yuzhang, Li Lisan, Nie Rongzhen andXiao San.[lxxi] Some of them married Western wives, for example Xiao San and Li Lisan.[lxxii] After World War I, France had lost a great number of men, so many Chinese students there could find a French wife easily, for example, He Siyuan and Zhang Daofan.[lxxiii]

In this period, the Chinese overseas knew more about Western society and gender orders. Evaluating the foreign female as the “Other” was common among Chinese males who studied abroad in the same period. For example, Lin Jinxian who toured to study in Western countries saw Western women were not as conservative as Chinese women, and he claimed that “western women were naturally with great affection”.[lxxiv] The gulf between new and old concepts first resulted in severe mental shock for the Chinese male. Mr. Qian Zhongshu, for instance, drew a subtle metaphor at the beginning of China’s opening:

“If doors and windows were widely open, it cannot say for sure that the old and weak inside the room will not catch a cold; if doors and windows were firmly closed, it was afraid that too many people inside the room may cause suffocation; if doors and windows were half open, maybe the effect will be like between refusal and consent in dating someone.” [lxxv]

Even relatively westernised Chinese like Hu Shi complimented the liveliness and openness of the western female on the one hand, but on the other said that the “female in China was in a higher status than the female in Western countries”.[lxxvi] In addition, the European female was healthy, beautiful and with white skin, and the discipline between male and female was not so strict, so the first outside temptation for students studying abroad was Western feminine charm. “As far as I saw and heard, there were a lot of students indulged in sexual desire.”[lxxvii] Some Chinese male students also married Western wives. When Jiang Liangfu was staying abroad, he was imperceptibly influenced by what he saw and heard. He wrote in his book Travel in Europe (Ou Xing San Ji), that:

“Most of our students studying abroad were people younger than 24 or 25, some of them were college graduates of China, some even did not go to college, all their cultural insights such as knowledge and view points were shallow and their moral characters were not mature. Once they moved to European and American countries with orders, laws and full of temptations, everything was too impressive to keep their mind tranquil, in such unrestrained and far-ranging places, how can they control themselves?”[lxxviii]

When they returned from abroad, students made reference to the Western countries, and initiated “Natural Feet Movement” and “Natural Breast Movement” for Chinese women.[lxxix] One famous scholar Hu Shi went to study in the USA, where he became acquainted with Miss Williams in America, and later wrote in his diary that “Since I have known my friend Miss Williams, I have greatly changed my opinion on females and social relations between males and females.”[lxxx] “The lady had such profound insight that no ordinary female could hold a candle to her. I knew many women, but only she had such a degree of thought and knowledge, courage and enthusiasm in one person.”[lxxxi] Zhang Zipin, who studied in Japan, also remarked that “I not only recognised the beauty of Japanese females at this age, but also was amazed by the development of female education and primary school education in Japan.”[lxxxii]

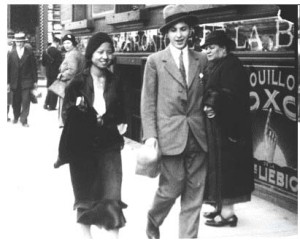

After the October Revolution, “learning from Russia” became popular, and Chinese students began to study in Russia. Jiang Jingguo, Li Lisan, Xiao San, Wang Bingnan and many others married Russian and German women. Some of these Western wives regarded China as their home since then, and obeyed Chinese notions of womanhood in their focus on assisting their husbands and teaching their children. At the fiftieth birthday of Jiang Fangliang, for example, her father-in-law Chiang Kai-shek gave her four Chinese characters, meaning virtuousness and piousness, to encourage her.[lxxxiii];With the further development of women’s education after the Wu Xu movement and the establishment of the Republic of China, more women went to study in Western countries in the 1920s and 1930s. For example, Qian Xiuling, who was fondly called by them “the Chinese mom of Belgium”, was one famous example. Qian Xiuling went to study in Belgium in 1929, and she obtained her PhD degree in Chemistry from the University of Leuven. She had traveled to Belgium with her brother and her fiancé. She broke up the relationship with her Chinese fiancé after they had lived together for a while, and fell in love with a Belgian man and married him. The happiness of the couple is clear in Picture 4.8. Even at that time, Belgian people rarely saw intercultural lovers; so many passerbys stared at this couple:

Picture 1.8 The lovestruck Qian Xiuling and her Belgian Man, 1933

Source: http://news.sina.com.cn/

Picture 1.8 The lovestruck Qian Xiuling and her Belgian Man, 1933

Source: http://news.sina.com.cn/

Historical records show that many famous Chinese men including scholars and scientists who had studied and worked in Western countries married Western women and, according to these, more Chinese men married Western women than the converse. Examples include Lu Zhengxiang[lxxxiv], Li Jinfa[lxxxv], Zhang Daofan[lxxxvi], He Siyuan[lxxxvii], Yan Yangchu[lxxxviii], Huie Kin[lxxxix], Liao Shangguo[xc], Yang Xianyi[xci], Li Fengbai[xcii] and Lin Fengmian[xciii]. There are also some other famous Chinese male intellectuals who married Western wives, such as: Dr. Xu Zhongnian (1904-1981, French linguist, writer); Wang Linyi (Sculptor); Zhang Fengju (1895-1996), a great Translator and Professor in Peking University, and Chang Shuhong (1904-1994), Chinese painter; He was the director of Dunhuang Art Research Academy, and he devoted his whole life to the preservation of the artworks at Dunhuang.[xciv] There were also many Chinese male scientists who married Western wives in this period, for example, Ye Zhupei[xcv], Xu Jinghua[xcvi], Qiu Fazu[xcvii], Bobby Kno-Seng Lim[xcviii], Huang Kun[xcix], Du Chengrong[c], Tiam Hock Franking[ci] and Liu Fu-Chi[cii].

B. Foreigners in China marrying Chinese, including intercultural marriages in Zu Jie (foreign concessions)

From an examination of available historical sources, there were only a few cases pf Westerners marrying Chinese in mainland China in modern times. The earliest formal interracial marriage between a local Chinese individual and a Westerner in modern China occurred in March 1862. An American Huaer (Frederick Townsend Ward) married Yang Zhangmei, daughter of Comprador Yang in Shanghai, who was very famous in the first year of the Tongzhi Period.[ciii] The second representative case of interracial marriage was between the American F. L. Hawks Pott, principal of Saint John’s University and Huang Su’e. They married in 1888. Huang Su’e was the daughter of Huang Guangcai, a Chinese priest of the Church of England, who later became the chief principal of Shanghai St. Mary’s Hall.[civ] The most famous interracial marriage in Shanghai was between the Jewish merchant Hardoon and Luo Jialin, in the Autumn of 1886. Luo Jialin herself was mixed race and was born in Jiumudi, Shanghai (between Street Luxiangyuan and Street Dajing). Her father Louis Luo was French while her mother, Shen, was from Minxian, Fujian Province.[cv] The third representative case was that of Cheng Xiuqi. In 1903, it was reported in the newpaper, Zhong Wai Daily, that a female missionary from Norway was doing missionary work round HuoZhou, Shanxi Province. She went on to marry Cheng Xiuqi, one of her believers, based on free courtship and changed her name to Yu Ying. Afterwards they went to Britain together and she gave birth to one daughter, before long they returned to China and set up Jie Yan Ju (Opium Rehabilitation Station) in Haizibian, Jin Cheng.[cvi] Shanxi province was always a closed and conservative area in China, but at that time it was even possible for Chinese-Western marriage to happen in such an area, there were also more intercultural marriages in other areas of China.

While there were only a few cases of this type of international marriages, intercultural marriages between local Chinese and Westerners in China was more common to see in Zu Jie (foreign concessions). These intercultural marriages were very representative, not only because Zu Jie had different laws from those generally applied in Chinese territories but also because its special and mixed cultures there. China was gradually becoming a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society in the 19th century, and many districts in cities including Shanghai were classed as leased territories of the western powers. In the modern leased territories where Chinese and foreigners lived together, there were some interracial marriages, a few of which were formal but many were informal (not registered but existed as de facto-marriages). In the following section, Shanghai will be taken as an example of international marriages between local Chinese and Westerners in China as it was most famous for Zu Jie.

At present, the earliest thesis recording intermarriage between Chinese and foreigners in Shanghai settlements was Sino-American Miscegenation in Shanghai written by Herbert Day Lamson in 1936. This thesis utilised marriage registration files from 1897 to 1909 from the American consulate in Shanghai and studied intermarriage between Chinese and Americans at that time in Shanghai.[cvii] According to the population records of the consulate, during the three decades from 1879 to 1909, there were 34 cases of interracial marriages between American husbands and Asian wives, among whom were 8 Japanese women and the rest comprised 26 Chinese women. There was no case of a Western wife married to an Asian husband. Of the 26 cases in 1930, there was less than one case of intermarriage each year. The jobs of the 34 Americans marrying Asian women are listed as follows: 11 seamen, 2 policemen, 2 sailors, 3 customs officers, 1 engineer, 1 missionary and 14 with indeterminate jobs.[cviii] During the 8 years from 1910 to 1918, there were 202 marriages on the records of the US consulate in Shanghai, among which there were 18 Asian wives including 6 Japanese, 1 Philippine, and 11 Chinese. From 1920 to 1922, there were 217 cases of registered marriages, while from 1930 to 1932, there were 236 cases. In these 6 years, there were 453 cases in all, among which only one was an American white woman with an Asian man, a Philippine in that case. There were 10 cases with Chinese or Japanese women, the proportion of which went down in comparison to previous years. The reason might be that in these registered marriages the number of white women increased. During this period, the Russian population and the prevalence of Russian women increased rapidly in the French concession and the International Settlement. For these American white men, especially those with low incomes such as seamen, sailors and customs officers, Russian women were more popular than Chinese or Japanese women. Most of the Russians in Shanghai were of low economic status, which increased the possibility of marriage between Russian women and Western white men from the lower classes. These Russian women sang or danced in the night clubs, and to some extent interacted more with the white men than did Asian women, which also increased their chances of marriage with white men.[cix]

There were materials about 9 cases of interracial marriages in the Shanghai Archive relating to the English, among which 2 were between Chinese men and Western women (one couple got divorced less than a year after their marriage), and the other 7 were all between Western men, mostly English, and Chinese or Korean women (one divorced).[cx] H. A. Martin, British Irish, married Ms. Tan of Guangdong who lived in Shanghai. The date of their marriage was not clear, but she gave birth to a son, Martin, in 1909, and lived at 214, Huashan Road. AnnaM. Meyer, a German, married Li Amei on the same day. In 1911 they had a daughter and lived in 20, Lane 148, Guba Road. Limbach, a German, married Ms. Gao in Qingdao. The date of their marriage was not clear, but they had a son in 1913. In 1915 they moved to Shanghai, and Limbach later became a professor of Tongji University. Isaiah Fansler was an American who was first a seaman stationed in China. He married Tang Yushu, a Chinese woman in 1939. Yao Runde, a Chinese man, married a Swiss woman in Switzerland. They married in 1944 and later they returned to Shanghai. In 1945, they divorced. Francisco Garcia, an Englishman, had a wife named Wang Aizhen, a native of Ningbo. The date of their marriage was not clear, and they lived on Route Lafayette. In 1946 they had a son and in 1947 they divorced. Charles A lverton Lamson, an American, married Li Quanxiang, a Korean woman. In 1946, they married in Shanghai, and lived on Daming Road. In 1947 they divorced. Rolf Smion, stateless, held an alien resident certificate and was a dentist. He married Song Aili from Haiyan, Zhejiang Province in 1947, and lived on Zhaofeng Road. Tan Boying, a Chinese man, married a German woman, H. Schenke, the date of their marriage was not certain. They had a son and a daughter, and lived on Yuyuan Road.[cxi]

Judging by the evidence of transnational marriages and cohabitation in the Shanghai concessions, at the end of the 19th century the phenomenon of more Chinese men marrying Western wives was being replaced by a phenomenon of more Chinese women marrying Western husbands. Among those foreigners in Shanghai, there were many single without families, who had a lot of opportunities for contact with Chinese women. This would inevitably result in many informal marital relations between Western white men and Chinese women. Not only in the early days of Shanghai but also in the Ningbo concessions, there had already been examples of Westerners in Shanghai, who had a children with their Chinese maids. For the English, it was very common to have a Chinese concubine. In 1857, Herder, a translator in Britain’s Ningbo consulate then and later Inspector General, lived with a Ningbo woman, A Yao. They lived together for 8 years in all. In 1858 or 1859, 1862 and 1865 they had three children who were then sent to Britain by Herder. Of humble origins, A Yao was a respectable woman. Her union with Herder transpired through introduction by compradors or other others. Xun He, a colleague of Herder, bought a Chinese girl as a concubine soon after he came to China. Another colleague of Herder in Britain’s Ningbo consulate, Meadows also had a Chinese wife.[cxii]

According to Bruner, John King Fairbank, and Richard J. Smith, one of the necessary conditions of high-class life for Westerners in China was to have a Chinese woman. This kind of woman was actually a walking commodity, which could be bought or sold by any foreign merchants.[cxiii] “At that time, the price for a foreigner to have a Chinese concubine was about 40 silver dollars” according to Herder.[cxiv] Powell, an American who lived in Shanghai temporarily, described the situation of formal or informal interracial marriages in Shanghai as “Shanghai could be considered as a city of men”. Nine out of ten foreigners in Shanghai were bachelors, and therefore many friendly relationships developed and resulted in numerous international marriages, which even the American Marine Corps quartered at Shanghai took part in. “Once I asked a chaplain of the Marine Corps whether these marriages were happy or not. He answered ‘just like other marriages’. I became to wonder if his answer had a little irony in it.”[cxv] For the foreigners in modern Shanghai, especially those single Western businessmen, it was very common to have informal marital relations with Chinese women. According to Bruner, foreign businessmen could easily buy Chinese women in China, and therefore many of them were registered single on the household registration form. These churchmen did not deal with commodities and had no comprador, and as a result they quickly brought their wives to China as well.[cxvi] But why are there so few materials documenting these events? The story of Herder’s diary easily demonstrates the reason. Although the diary was published, Herder deleted all the contents about his cohabitation with A Yao in Ningbo while he reorganised his diary which was left with a large gap. Afterwards, Herder was reluctant to discuss this experience and he never admitted that he was the father of the three mixed-race children in public, despite the fact that he always looked after them financially and loved them very much.[cxvii]

In general, there were not many interracial marriages between the Chinese and the Western whites in modern Shanghai. According to Xiong, it was estimated that after being opened as a commercial port between 1843 and 1949, there were no more than 100 cases of formal marriage between the Chinese and Westerners in Shanghai over 106 years. Judging from the aspect of time, there was a tendency towards a gradual increase from far to near. Maybe this was related to the increase in foreign settlers, or the increasing communication between different races.[cxviii] For a long time, English settlers in Shanghai resolutely were opposed to marriage with the Chinese. In 1908, the English envoy in China sent out a confidential document, harshly condemning marriages with the Chinese and threatening to expel the violators of this rule from the English circle forever.[cxix] According to research by English scholar Robert Bickers, before 1927, policemen in the English police station, Shanghai Municipal Council, were prohibited from marrying the Chinese. In 1927, the general inspector of the station stated that transnational marriages did not meet the interests of the police force.[cxx] In 1937, the president of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation said that marriage between foreigners and local Chinese mixed race people was absolutely intolerable. If anyone did this they would be formally fired by John Swire & Sons Group and other big companies.[cxxi] The community of English residents in Shanghai had a harsher restriction upon English women as they believed it was treacherous for noble English women to marry humble Chinese men. One English man wrote in his letter to his sister that “if you dared to have an affair with Asian men in Shanghai, you would never stay here well.”[cxxii] In the middle of the 1930s, the Department of the Far East under the English Foreign Ministry tried its best to persuade those English women who had an intention to marry Chinese men not to do so. In the official book, it warned that marrying Chinese men may cause loss of British nationality, which meant that those British women who married Chinese men would no longer be protected by British law in China.[cxxiii] Compared with the upper-class British residents, the restrictions upon the lower classes on marriage were looser, and there were some instances of marriage between lower-class British and Chinese. In 1927, policeman Parker in Shanghai Municipal Council applied to marry a Chinese woman. After the committee’s examination, the woman’s parents were believed to have high status, and the marriage was permitted. However this policeman lost any prospect of future promotion. In 1934, relevant departments in Shanghai issued martial certificates to 6 Chinese women all of whom had British husbands.[cxxiv] Therefore, it could be noticed that before wider contact was opened up between the Chinese and Westerners, both sides sought to protect their long cultural traditions of which they were very proud. After the Opium Wars, despite the Chinese defeat on the battlefield, their deep sense of cultural superiority was not lost. Equally, Westerners from Britain, France, the USA and other countries living in Shanghai also claimed to be the superior races on a cultural level. Compared to the British, the Americans had a more tolerant attitude towards marriages with the Chinese, but they also basically opposed it.[cxxv] Therefore, in general, both sides rejected marriage with each other.[cxxvi]

In respect of transnational marriages in the modern Shanghai concessions, if it is said that there was not a high rate of Western men marrying Chinese women aside form a small number of cases, then it was quite rare to see examples of Western women marrying Chinese men. This was because if an American woman married or just was engaged to a Chinese man, the general reaction of other Americans was to question why she wanted to marry a Chinese man, and ask whether she could not find a more appropriate husband in the USA, regardless of how well-educated the Chinese man was. Other Americans would claim it would be unfair for their children.[cxxvii] However, the situation was quite the opposite to that of transnational marriages among the Chinese in America. At that time in America, nearly all of the transnational marriages relating to the Chinese were exclusively between Chinese men and Western women. In 1876, there had already been 4 or 5 cases of Chinese men marrying American wives in San Francisco. In 1885, there were 10 families of Chinese husbands and American wives there. From 1908 to 1912, there were 10 marriages of white women marrying Chinese men in New York, without a single case of marriage between an American man and a Chinese woman.[cxxviii] Mr. Wu Jingchao who researched this issue asked,

“Has there been any American man marrying a Chinese wife? In the materials I have collected, there has never been such a case. Of course, we know there were many cases of foreign men marrying Chinese women, but all of these happened in China rather than America. Only several years before, a Chinese woman, being an actress in some Hollywood movie company, fell in love with an American man who never married her. Later he said to others that I could be friends with the Chinese woman. As for marrying her, it was impossible. Even if I would, my mother would definitely disapprove and my friends may also oppose.”[cxxix]

In Shanghai, intercultural marriages were between Western men and Chinese women, while in America such marriages were between Chinese men and Western women.[cxxx] Although the trends seemed diametric opposites, they reflected the same truth that if the migrants only took a tiny proportion in comparison with the natives it was men who first broke through interracial marriage restrictions. It mirrored the situation at the end of the Qing Dynasty when it was mostly Chinese men, especially those who had experience of staying in Western countries, who married western wives.[cxxxi]

C. Chinese labour workers who were sent to Western countries on a large scale in modern China.

Besides overseas study, overseas trade dealing and working abroad also become important ways leading to Chinese marrying Westerners in their countries. “Open up the Northeast of China”, “Moving to the West”, and “Sailing to Southeast Asia” are three great migrations of population in Chinese modern history. In the past, from the cultural perspective, the Chinese nation was an agricultural one, whose primary characteristics were sticking to one’s land and living a peaceful family life.[cxxxii] Indeed, great courage was required before they decided to explore and strive in the new world. As the old saying goes, it is better to be a dog in peace than to be a man in turmoil. The Chinese nation emphasises harmony between men and nature and a peaceful life, therefore, the Chinese would generally not leave their hometown without special reasons, such as extreme life pressures or war.[cxxxiii]

At the demise of the federal dynasties in Chinese history, the common people and the fallen nobles of the previous dynasties started to drift abroad to Southeast Asia to escape the conflict. Due to its geological closeness, Southeast Asia became the migration destination and shelter of Chinese migrants. The drifting population would come to Southeast Asia despite the long distance to strive to make a living, this period was called “Sailing to Southeast Asia” in Chinese history.[cxxxiv] Besides the Southeast Asian countries that were comparatively close to china, the Chinese also moved to western countries for the sake of employment.[cxxxv] Apart from working as labourers, the Chinese also did business in Western countries.[cxxxvi] Among them many achieved huge success in their businesses, surprising the white people in mainstream society who later looked at them with new eyes.[cxxxvii] These Chinese stayed there because of their businesses, and some of them married local people.

In the 1840s and 1850s, a large amount of Chinese migrants began to travel to the American West to seek gold, where they also assisted in building railways. Chinese migrants first appeared in 1848 when they found gold in California prompting others to join the Gold Rush. The earliest Chinese migrants came from Guangdong province, and were peasants from different villages who sailed to “Gold Mountain” after borrowing money or selling themselves to human traffickers as cheap labour. The “Gold Mountain” referred to California in America. According to historical records, in February, 1848, that is, two months after the discovery of gold mines in California, two Chinese men and a woman sailed across the Pacific Ocean from Canton to San Francisco in California in the ship, the American Eagle, becoming the earliest Chinese migrants to land and stay at “Gold Mountain”. Two years later, different groups of Chinese came successively, among whom most quickly went to the gold mine, Sutter’s Mill, to seek gold, and a few gathered in Dupont Street and Sacramento Street at that time in San Francisco. Later “China Town” gradually evolved from this. In 1865, the number of Chinese migrants amounted to 50,000, 90% of whom were young men. They then came to the “Gold Mountain” to build railways instead of seeking gold.[cxxxviii] Many Chinese men could not find Chinese wives in the USA at that time, so it prompted some of them to find local wives; many of them married African American women.[cxxxix]

A similar movement of Chinese labourers happened in Europe, albeit with some differences. In 1914, World War I had taken place, resulting in the deaths of tens of millions of European labourers. Consequently, during the War, a great number of Chinese labourers were sent to Europe to supplement the work force of these countries.[cxl] In respect of France some margin studies found that many Chinese male labourers married French women at that time. Dr. Xu Guoqi showed that many French women married Chinese labourers during the First World War.[cxli] During the War, 140,000 Chinese labourers came to Europe to help the Allied war effort, 96,000 of them were allocated to the British army, and 37,000 were depatched to France. Many French men had died at war, so the French women welcomed Chinese men, and more than 3,000 Chinese labourers married French women at that time.[cxlii] Although Chinese male labourers were maltreated and beaten, and were not allowed to leave the camp, they still “managed to escape at night, for one night… Also there were problems with French women”.[cxliii] “Some Chinese male labourers formed attachments with French women and oft times children were born. At a later date they returned to China with their French wives and children. The exact number is not known, but French sources quote about 30,000,[cxliv] which appears excessive.”[cxlv]

With regard to Russia, as early as the 1860s, it had speeded up developing its territories in the far east, and built cities, roads, ports, railways and communication lines, in the process recruiting many foreign labourers, of which Chinese labours made up the greatest number.[cxlvi] From 1891 onwards, Russia recruited Chinese labourers to build the Siberian Railway.[cxlvii] Russia suffered great losses in the War, and lacked labourers as a result, so it continued its policy of recruiting Chinese labourers.[cxlviii] Between 1915 and 1916, Russia reached a high tide in recruiting Chinese labourers. In 1917, the October Revolution occurred in Russia, and Tsarist Russia was overthrown by the Bolsheviks. About 200,000 Bielorussians went into exile to China because of the threat of the Russian 1917 Revolution, and many Bielorussians settled down in China and even married Chinese.[cxlix] At that time, there were 230,000 Chinese labour workers in Russia, who participated in the revolution to “protect soviet” as Chinese labour troops. Many Chinese labour workers in Russia at the time married Russian women, and this became commonplace among Chinese labour workers.[cl]

Besides those working as labourers, the Chinese also did business in Western countries. For example, in America, in 1870, the Chinese prospered in business although Chinese vegetable venders still sold their goods on the San Francisco streets carrying a horizontal stick on their shoulders. The laundries in downtown areas were mainly occupied by Chinese laundrettes. Many Chinese began to work in industries of quantity production, mainly in the four industries of shoemaking, fur textile, tobacco, and clothes-making. Until 1870, the number of Chinese workers amounted to half of the total numbers working in the key four industries in this city. Their employers were mostly Chinese as well. Until the 1970s, there were about 5000 Chinese businessmen in San Francisco.[cli] Among them many achieved great success in their business, surprising the Westerners around them and changing their perception of them.[clii] In Australia, many Chinese men also came to settle there for business reasons (See picture 4.11). These Chinese stayed there because of their businesses, and some of them married local people.

Picture 1.10 Chinatown in America of 19th Century

Source: http://www.boonlong.com/

Picture 1.11 Australian wife Margaret and her Chinese husband Quong Tart and their three eldest children, 1894

Source: Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists 6/16/4 [cliii]

D. Intercultural marriages and Migration caused by the Chinese Civil War

Civil wars create refugees who flee across international borders to safer havens.[cliv] The Chinese Civil War (CCW), from 1945 to 1949, was fought between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It was one of the bloodiest and most violent wars in the modern world, and 6 million soldiers and civillians were killed.[clv] The end of the CCW produced a large wave of refugees from China to Western countries, such as the USA. Of all the Chinese migrants that moved to foreign countries, the refugees created by the CCW were the greatest in number. It was a very intense and sudden event in modern Chinese history. These departing groups were quite different from the peasant labourers who had pioneered the initial Chinese migration to the USA. These refugees included members of the intellegentsia, the upper classes, and families of wealth. There were also a number of Chinese students studying in the USA who were afraid of returning to China because of the changes in the political system. Many of them were subsequently granted immigrant status.[clvi] These sudden and numerous fleeing Chinese people became the protagonists of CWIM in this period. As stated by Fink, the most important functional factors imposed by civil wars are spreading refugees into other States, presenting ethnic, linguistic or religious confreres in the destination countries, and sharing ideologies or alliances between the participants and potential patrons.[clvii] By these means, these groups of Chinese people had opportunities to marry Americans, resulting in some CWIMs during this period.

1.2.2 Government Intervention in Both China and Western Countries

Although it emerged as a social entity during this period, marriage between Chinese and foreigners also encountered opposition from the outside world, both from Western and Chinese governments. Westerners held racial biases against the Chinese, and so they set up various obstacles inhibiting marriage between the two cultures. Where Chinese men married foreign women, western countries tended to object to and discriminate against them. This could be seen as a miniature playing out of the male-dominated world, that is, men tried to prevent women of their race from marrying outward. This section will look at governmental intervention and the role that governments played in the CWIM of both China and the West in modern times.

For Western countries, in the 19th century, the ideology and government policies of Great Britain and the USA took a repellent or, at least, inhibitory attitude towards interracial marriages in their own realms.[clviii] For example in the USA, from the middle and late period of the 19th century and the first two or three decades of the 20th century, there were about 11 states in the USA prohibiting marriages between Americans and Chinese, including Arizona, California, Missouri, Oregon, Texas, Utah and Virginia. For some of these States, especially those in the south, they were always hostile towards people of colour, whether black or yellow. For those States in the west, such as California, where there were many Chinese immigrants, there had been movements against Chinese labourers and they were hostile to the Chinese. As we can see from Figure 4.8, there were almost no Chinese women in Chinatown, San Francisco in the 19th century. The early Chinese arrivals in USA were primarily young males, but the abounding prejudice and discrimination at that time in the USA forced the majority into segregated Chinatowns where opportunities for contact with non-Chinese females were extremely limited. Californian miscegenation laws were implemented from 1850 and these prohibited marriage between Caucasians and Asians, Filipinos, Indians, and Negroes. These laws were no overturned until 1948.[clix] Even in the 1930s, Chinatowns in the USA were still seen as a ‘man’s town’ or a ‘bachelors’ society’.[clx] In 1878, the California State Council approved an amendment prohibiting the Chinese from marrying whites. In 1880, Californian Civil Law prescribed that marriage certificates were not allowed for whites with blacks, Mulattos or Mongolians. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Law prohibited marriage between Chinese and whites. This was first issued in California and later spread around the whole USA, becoming a national law. In 1922, the Cable Law restricted and prohibited marriage between Americans and Asian migrants, and it warned that they would lose their civil rights if they married Asians.[clxi] In addition, a female‘s citizenship was not linked to her husband’s, and this was mainly in order to prevent Chinese women from immigrating to the USA by marrying Chinese men who were born in America. Because of these regulations amongst other factors, most of the Chinese American men in the USA at that time did not have a wife. According to the data of Los Angeles from 1924 to 1933, only 23.7% of Chinese men there had non-Chinese wives, and at that time the male-to-female ratio among Chinese Americans was 9:2, so most Chinese men did not have a wife.

The situation was similar for other Asian people in relation to marriage. The Japanese had followed the Chinese in coming to America, and, in the early days, they had a very low intermarriage ratio. According to the data of Los Angeles from 1924 to 1933, only 3% married Japanese men had non-Japanese wives. The Japanese in America also suffered under the discriminatory laws and from the social discrimination encouraged by them. In 1923, the organisation, “Native Daughters of the Golden West” warned white women that “these days, some Japanese men with a good family background are found to peek at our young women, and they want to marry them.” The president of the California Control Society even thought that the Japanese intended to conquer the USA with intermarriages as a key component of their plan.[clxii] Because of this cultural background, the American white people in China at that time always held an objective attitude toward marriage with people of Asian colouring. Some English scholars once tried to discuss this question from a sociological respect. In 1982, some Japanese wrote to Spencer, the famous English scholar, and asked about his attitude towards interracial marriage. In his reply, Spencer talked about his opinions and mentioned that the US prohibited the entrance of Chinese. He approved of this on the basis that if the US allowed the Chinese to come and go at their will, there would only be two options for them. One was that in the US there would be two separate classes, the white and the yellow, and they would not intermarry. The other was interracial marriage which would lead to many undesirable hybrids. In his view, no matter which way it would be, the result was not favourable.[clxiii] Spencer’s attitude had great influence, and well into the 1920s and 1930s, many westerners were of this opinion.

Australia provided another example. Western colonists considered the Chinese as different from them and believed they would be unable to integrate into white society for cultural, biological, language and racial reasons. The Australian Colonial government also implemented policies to impose race boundaries between whites and Chinese.[clxiv] These policies were not only confined to the political sphere but were extended to interracial intimate relationships. As stated by McClintock, they “gave social sanction to the middle class fixation with boundary sanitation, in particular with the sanitation of sexual boundaries”.[clxv] White women’s bodies and sexuality were considered by policy makers as very threatening and destabilising to the established boundary order.[clxvi] As McClintock suggested, white women were seen as “the central transmitter of racial and hence cultural contagion”, and so they must be blockaded from men from other races.[clxvii] The intimacy between white women and non-white men brought great anxieties for the colonial government. The anxieties and indignation could be seen at the very early stages of 1850. Early debates of the 1850s on Chinese migration to Australia were particularly concerned about the possibility of the ‘destruction of the white race’ through sexual relations between Chinese men and white women, although there were only one or two cases of marriages between Chinese men and white women in Australia at that time.[clxviii]

Western countries not only constrained Chinese-Western marriages in their own realms, but they also wantonly interfered with and obstructed Chinese-Western marriages in China, and they demonstrated their powers in attitudes on intercultural marriages. In 1899, an American priestess and doctor in Guangdong married a Chinese man, Lan Ziying, which unexpectedly caused a big stir. Two American people in Guangzhou wrote to the American Embassy to suggest a doctor check whether the woman was suffering from a psychiatric disorder. This is a clear example of racial prejudice. The American consul in Guangzhou did not interfere as “there has been no obstruction for a foreign woman to get married with a Chinese.” (However, in some States of America, there were laws prohibiting marriage between whites and Chinese).[clxix] In 1911, some Western women eagerly asked the British consul in Chengdu to intervene in the marriage between a British women, Helen, and Hu Jizeng in Sichuan. They said that Hu already had a wife, and had committed bigamy within Western terms. The British consul negotiated with Wang Renwen, Sichuan Vice Governor, and asked him to punish Hu according to the law. Wang said that under Chinese law, having two wives was not a crime. Finally the British Embassy in China realised they could not prevent the marriage but warned Helen: “If you don’t have a divorce and return home, it will be regarded that you give up your British nationality”. However, using Chinese terms, she said, “I would like to be his concubine even till death”. Unexpectedly, the angry envoy replied, “Britain would never permit you to be a concubine. If you are a whore, you are not permitted to stay in China.[clxx]” , In judging the case, Ta Kung Pao commented: