You incorrect: Dating app statistics disaggregate

| DATING ISRAELI GIRL ASIAN | |

| IM DATING A GIRL WITH A PENIS | |

| TOP DATING APP IN DES MOINES FOR 30-40 | |

| CARMEL CA WOMEN DATING |

Bridging Gender Data Gaps in Latin America and the Caribbean: Technical Report

View/download the print version (PDF) of this report

See also the Methodology Report and Country Profiles

About Open Data WatchOpen Data Watch is an international, non-profit organization of data experts working to bring change to organizations that produce and manage official statistical data. We support the efforts of national statistical offices (NSOs), particularly those in low- and middle-income countries, to improve their data systems and harness the advancements of the data revolution. Through our policy advice, data support, and monitoring work, we influence and help both NSOs and other organizations meet the goals of their national statistical plans and the SDGs. Learn more about Open Data Watch at www.opendatawatch.com

About Data2XData2X is a technical and advocacy platform dedicated to improving the quality, availability, and use of gender data in order to make a practical difference in the lives of women and girls worldwide. Working in partnership with multilateral agencies, governments, civil society, academics, and the private sector, Data2X mobilizes action for and strengthens production and use of gender data. Learn more about Data2X at www.data2x.org

About UN ECLACThe United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) is one of five regional commissions of the United Nations. It was founded with the purpose of contributing to the economic development of the region, coordinating actions directed towards this end, and reinforcing economic ties among countries and with other nations of the world. The promotion of the region’s social development was later included among its primary objectives. The ECLAC Division for Gender Affairs plays an active role in gender mainstreaming and advancing women’s autonomy within regional development in Latin America and the Caribbean. It works in close collaboration with the national entities for the advancement of women in the region, civil society, the women’s movement, feminist organizations and public policymakers, including national statistics institutes. Learn more about ECLAC at https://www.cepal.org/en

#BridgetheGap

|

Executive Summary

Bridging the Gap: Mapping Gender Data Availability in Latin America and the Caribbean assesses the availability of 93 gender indicators, their disaggregations, and their frequency of observation in international and national databases and publications. It reports on the availability of gender data in Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Paraguay, and with the assistance of our partners at the UN Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC), it documents the availability of statistical indicators to support gender development plans in the five countries.

Gender data are indicators of the status and welfare of women and girls or, when sex-disaggregated, indicators of pertinent differences between men and women. These indicators — if produced regularly and to a high standard — can be used to develop and implement policies and monitor results, delivering on commitments to achieve equality and opportunities for women.

In 2018, Data2X and Open Data Watch conceived a study that would offer national statistical offices, international statistical systems, development partners, and others involved in measuring and monitoring the progress of the world’s women and girls a more complete understanding of where gaps in gender data exist, why such gaps occur, and what can be done to fill them. The resulting technical report, Bridging the Gap: Mapping Gender Data Availability in Africa (Data2X, Open Data Watch, 2019), provided insights into those questions and moved the development community one step closer to producing high-quality and policy-relevant gender indicators to inform better decisions. This study builds on the experience of the previous study but shifts the geographic focus to Latin America and the Caribbean.

The 93 indicators selected for this study come from the list of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators or were recommended by UN Women to supplement the SDGs. Data gaps were examined in four dimensions: availability, granularity, timeliness, and adherence to standards. Using official national and international sources, study assessors recorded whether the indicators exist in any form, whether they were sex-disaggregated, and whether there were additional, advised disaggregations such as geographic location, age, income level, or disability status. Indicators were checked for adherence to international standards. Also recorded was how recently an indicator was produced and its frequency.

The availability of gender indicators was assessed at the international, national, and microdata levels. Data in international databases have been reported by countries and reviewed by custodian agencies. They generally, but not always, follow international standards for the computation and presentation of the indicators. Data in national databases may follow methodologies different from those in international sources but may still provide useful information for citizens and governments. Exploration of the microdata from censuses, surveys, or administrative records used to produce the most recent estimate of the indicator and their associated microdata reveals what instruments are being used to produce gender indicators. It may also reveal underutilized data resources or the need for higher frequency data collection. By better understanding the production and availability of gender data at these three levels, we can draw specific lessons on how to fill gender data gaps.

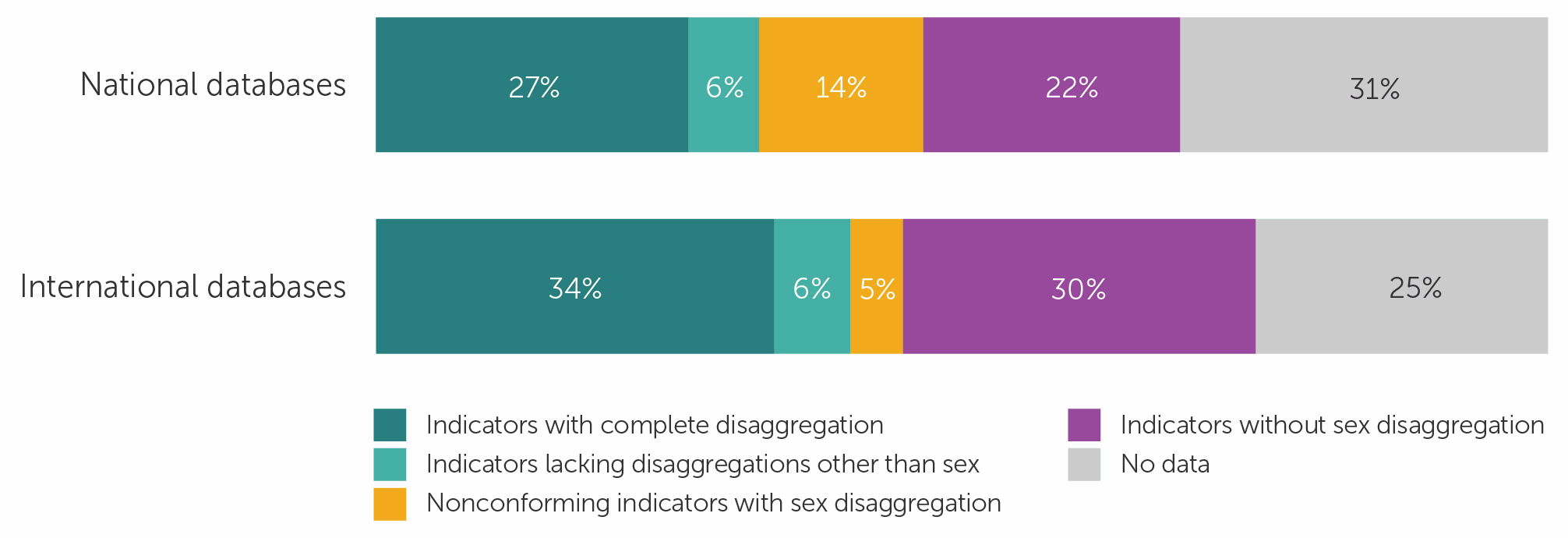

Large gaps remain in the statistical record. The study revealed that 53 percent of gender-relevant indicators are missing or lack sex-disaggregated data at the national level and 55 percent at the international level. In international databases, 30 percent of the indicators lack any sex-disaggregation and 25 percent are missing data entirely. In national databases there are more missing observations (31 percent) but a smaller proportion —22 percent — lack sex-disaggregation. This persistence of large gaps in both international and national databases points to the need for a coordinated effort to improve data collection and adopt common standards for the compilation of indicators.

The study looks at the availability of gender data across six development domains: health, education, economic opportunity, political participation, human security, and the environment. None of the six domains assessed have more than 68 percent availability of sex-disaggregated indicators, showing that even where data availability is highest, significant gender data gaps exist. The education domain has the highest proportion of sex-disaggregated data. Environment has the lowest proportion of sex-disaggregated data, with only seven percent at the national level.

Gender data availability varies between international and national databases as well as between countries themselves. There are some data for 75 percent of gender indicators in international databases and for 68 percent in national databases. In national databases, Paraguay and Jamaica (59 and 60, respectively) produced the fewest gender indicators, while Costa Rica (73) produced the most. Frequency of indicator production is highest in Colombia, where there was an average of 5.7 observations per indicator, and lowest in Paraguay, with only 2.1. Variations in data availability and capacity to fill data gaps shows that countries make difficult choices in their data production as a result of resource limitation.

Administrative sources are a potential source of high-quality sex-disaggregated information giving insight into the lives of women and girls that cannot be achieved with surveys. However, to play this role, improved documentation and more accessibility is required. Many of the indicators studied here still depend upon national or internationally sponsored sample surveys. These data sources, while of high quality, carry with them the limitations of any survey exercise: they are expensive, intermittent, and cannot provide resolution at small scale.

The results of this study document gaps in datasets needed to sustain progress toward gender equality, but even if these were to be filled, the data still need to be used in decision-making processes and incorporated in government policies. Going beyond the previous Bridging the Gap assessments, this study also evaluates national gender policies for how they include data in their planning and decision-making processes. Our findings show countries could improve their planning and decision-making process by either creating new plans or updating old plans with specific targets tied to measurable indicators. Further, providing easy access to these data through data portals, would increase public awareness and provide important evidence of progress towards targets and goals.

In addition to the results of the assessments and the findings described in this report, the study produced an expansive dataset that will be used to inform further research and analysis about gender data availability and accessibility. A companion volume documents the study methodology.

Introduction

Data gaps are voids in our knowledge of the world and the people and communities who live in it. They limit our ability to understand the world as it is and to plan for change. In the case of gender data, these gaps limit our knowledge of the status and well-being of women and girls in countries around the world. Just as gender data are essential for designing and monitoring programs to improve the well-being of women and girls, knowledge of the location and persistence of gender data gaps is needed to design programs and mobilize resources for filling those gaps.

The terms gender data and gender indicators are used interchangeably in this report to refer to indicators that are defined uniquely for women or that provide sex-disaggregated data. In addition, disaggregations other than sex, such as age, location, refugee status, or disability may also be defined for some indicators. This study reports on the availability of 93 gender indicators, their disaggregations, and their frequency of observation in international and national databases and publications in five countries from the Latin America and Caribbean region. Data2X and Open Data Watch conducted this study to provide a quantitative assessment of availability of statistical indicators that are of particular relevance to measuring the living conditions of women and girls. The study also documents the microdata sources (censuses, surveys, and administrative records) used to construct the 84 gender indicators included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The study results show that, on average, sex-disaggregated data are available for only 47 percent of the SDG gender indicators in national databases in the five countries studied. These gaps are extensive but not uniformly distributed. Some indicators are available in every country over the period 2010 to 2019. But other indicators occur only sporadically, and large gaps exist in every country’s gender statistics. Using the results of this study, we can identify which countries and indicators have the largest gaps and suggest methods for filling them.

Background and previous studies

In 2014, Data2X published the first comprehensive report on the availability of gender indicators, Mapping Gender Data Gaps (Buvinic et. al., 2014). The study included some of the 52 indicators that comprised the Minimum Set of Gender Indicators proposed by the United Nations Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Gender Statistics (UNSC, 2013). The study found that, “globally, close to 80 percent of countries regularly produce sex-disaggregated statistics on mortality, labor force participation, and education and training. Less than a third of countries disaggregate statistics by gender on informal employment, entrepreneurship, violence against women, and unpaid work.”

Following the publication of Mapping Gender Data Gaps, Data2X and Open Data Watch (2016) identified a set of 20 gender indicators that were “ready to measure,” meaning that the indicators were available or the necessary microdata sources existed to construct them. The study drew on the World Bank’s Gender Data Navigator (GDN) to identify the surveys with sufficient data for constructing the indicators (World Bank, n.d.). Notwithstanding the availability of survey and administrative data, many gaps in these and other gender indicators persist.

To provide a more complete tabulation of gaps in gender data, Open Data Watch (ODW) and Data2X undertook a study of an expanded set of indicators in 15 low- and middle-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Bridging the Gap: Mapping Gender Data Availability in Africa, ODW, 2019). The study examined the availability of 104 gender indicators in national and international databases over the period 2010 to 2018. It recorded the years in which the indicators were available, their disaggregation (by sex or other specified characteristics), and information derived from their metadata (where available) on the sources of the underlying data. It was also noted whether the published indicators conformed to international standards including frequency and timeliness.

In the countries studied, 48 percent of the gender indicators were missing or lacked sex-disaggregated data at both international and national levels. In international databases, 22 percent of the indicators lacked any sex-disaggregation and 26 percent were missing data entirely. In national databases there were more missing observations (35 percent) but a smaller proportion — 13 percent — lacked sex-disaggregation. Indicators were classified into six development domains. The health domain had the highest proportion of sex-disaggregated data, with 73 percent of the indicators sex-disaggregated at the international level. Environment had the lowest proportion of sex-disaggregated data, virtually none.

Contribution of the current study

This study builds on the results from previous publications but shifts the geographic focus to Latin America and the Caribbean. It reports on the availability of gender data in Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Paraguay. The countries were selected in consultation with the Economic Commission of Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). The countries are, on average, wealthier and have more developed statistical systems than those included in the Africa study. The study uses a revised list of gender indicators, including an additional 12 SDG indicators for which methodologies have become available. The assessments follow the same methodology used for the Africa study, but the time period has been extended from 2010–2018 to 2010–2019. (See Bridging the Gap: Methodology Report (ODW, 2020)). As in the previous study in Africa, this study has produced a precise audit of the publicly available gender indicators for the selected countries. In doing so, it provides a blueprint for filling the gaps in these and similarly situated countries.

Previous work Latin America and the Caribbean

In the 2017 Annual report on regional progress and challenges in relation to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Latin America and the Caribbean, ECLAC presented a comprehensive diagnostic on the institutional architecture for monitoring statistical processes related to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The report considered the national statistical capabilities for the production of the Sustainable Development Goal indicators in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as the challenges posed to national statistical systems by new data ecosystems. Each year since then, the report had tracked the progress for monitoring SDGs in the region with a focus on prioritizing regional needs as well as identifying actions to improve statistical production.

ECLAC has also analyzed the 2030 Agenda and the SDG indicators in light of the challenges and priorities for gender equality and women’s rights and autonomy in Latin America and the Caribbean. The 2030 Agenda and the Regional Gender Agenda: Synergies for equality in Latin America and the Caribbean highlights the interconnections between the goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda and the importance of taking an integrated approach to ensure that progress on some SDGs is not achieved by means that could impede the attainment of goals and targets associated with gender equality and women’s rights.

Identifying gender indicators

In March 2016, the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on the Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) submitted its proposed list of some 232 indicators[1] (IAEG-SDGs, 2016). The indicator list was subsequently partitioned into three “tiers”: indicators with an agreed methodology and reported by a majority of countries were assigned to Tier I; indicators with an agreed methodology but less well reported were assigned to Tier II; and indicators lacking an agreed methodology were assigned to Tier III. At subsequent meetings of the IAEG-SDGs, the tier classification has been revised and indicators have been promoted to higher tiers as new methodologies were proposed or more data became available.

The IAEG-SDGs (2019) has identified a “minimum set” of 54 SDG indicators that are “specifically or largely targeted” at women or girls. However, a number of these are among the SDG indicators that were classified by the IAEG-SDG as Tier III indicators because they lacked an agreed methodology and were not available for most countries (IAEG-SDGs, 2018). UN Women noted that “a less restrictive criteria where all indicators that are relevant for women and girls and can be disaggregated by sex are included would yield a greater listing of gender-relevant indicators.” Accordingly, Open Data Watch conducted a more detailed assessment and identified 36 additional Tier I and Tier II SDG indicators that are commonly published with sex-disaggregation or might be at a future date. UN Women has proposed a set of supplemental indicators to ensure that there exists at least one indicator for each of the 17 SDGs (UN Women, 2018). Open Data Watch selected nine of these indicators to include in the research dataset for this study.

Since the Bridging the Gap study in Sub-Saharan Africa, 11 Tier III SDG gender indicators have been upgraded to Tier II and one to Tier I. These indicators are included in the present study along with the nine supplemental indicators proposed by UN Women in 2018 but not included in the SDGs. To better focus on the indicators of current interest, indicators from the original UN Women Minimum Set that were not included in the SDGs have been dropped, leaving 93 gender indicators in the Latin American and Caribbean study, of which 84 are SDG indicators. For more information about indicator sources and selection, see the Bridging the Gap Methodology Report (ODW, 2020).

Typology of gaps in international and national databases

| 1. AVAILABILITY The study recorded the availability of data in international databases such as the United Nations Global SDG Database (UNSD, n.d.) and the World Bank’s Gender Data Portal or those of the specialized agencies of the United Nations. National databases and publications available online were also examined for instances of the specified indicators. For each indicator and country, the study assessors noted whether the indicator was available with sex-disaggregation and other disaggregations required by the SDGs; the number of observations available between 2010 and 2019; and the location of metadata describing the sources and methods used to construct the indicator. | |

| 2. LEVEL OF DISAGGREGATION Each indicator was assessed for whether it was fully disaggregated or if it lacked one or more required disaggregations. Indicators that lacked sex-disaggregation were recorded separately. | |

| 3. TIMELINESS AND FREQUENCY Indicators were assessed for their timeliness and frequency. Timeliness was measured from the date of the most recent observation and frequency by the number of observations available over the period of 2010 to 2019. | |

| 4. Adherence to standards Adherence to international standards is documented by the inventory of metadata recorded as part of the assessments. Indicators whose descriptions do not match their SDG definition were classified as “non-conforming” with their disaggregations recorded. A few examples include the following:

|

Microdata sources

The Bridging the Gap studies in Sub-Saharan African and in Latin America and the Caribbean link gender indicators to their microdata sources and provide a summary data page with a description of each indicator, documentation of the indicator produced by each country, and its microdata sources. Metadata reviewed during the indicator assessments were used to identify the censuses, surveys, or administrative records used to construct the indicators found in national databases. Survey questionnaires were examined as needed to clarify sources and the availability of disaggregations.

Study findings

Data quality and availability

Data quality depends on many factors: whether the data were properly collected and recorded; in the case of the survey data, whether the sample frame was well constructed and of sufficient size; and whether the construction of the indicator conformed to recognized standards and definitions. In this study, indicators available in national and international databases were assessed for the adherence to international standards as described by their SDG methodology or, for non-SDG indicators, as defined by UN Women.

For each indicator and each country, study assessors noted whether data for the selected indicators were available in one or more years between 2010 and 2019, whether the indicators were sex-disaggregated, and whether other disaggregations specified in their original description were included. The results were recorded separately for data found in international and national databases. The international databases studied are those maintained by designated custodian agencies such as the WHO, UNICEF, International Labour Organization (ILO), or the World Bank and the SDG Global Database. National data covered by the study included databases in online data retrieval systems such as data portals, online publications of national statistical offices or other government agencies, and nationally published research findings.

Indicators that fully conformed to their standard and included all prescribed disaggregations were classified as:

- AA (Available with all disaggregations)

- AF (Available but applicable only to women)

Indicators that conformed to their standard but lacked one or more of their prescribed disaggregations were classified as:

- BA (Available and sex-disaggregated but lacking other disaggregations)

- BF (Available, applicable only to women, but lacking other disaggregations)

- BX (Available but lacking sex-disaggregation)

Non-conforming indicators that were judged to be similar to or plausible proxies for the specified gender indicators were classified as:

- CA (Sex-disaggregated)

- CF (Applicable only to women)

- CX (Lacking sex-disaggregation)

Indicators with no observations over the 11-year period were classified as XX.

Table 1 shows the distribution of all 93 indicators by their classification in national databases. From a gender data perspective, indicators classified as AA, AF, BA, and BF can be considered of high quality. BX indicators, while conforming to standards, do not provide necessary information on the sex of the subjects. CA and CF indicators may be considered to be of lower quality although they provide gender-relevant information. CX indicators sit lowest on this scale as non-conforming and lacking sex-disaggregation.

Table 1: Number of indicators in national databases by availability and country

| Indicator availability | Colombia | Costa Rica | Dominican Republic | Jamaica | Paraguay | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 5 | 23 | 18 | 14 | 20 | 16.0 |

| AF | 5 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7.6 |

| BA | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6.2 |

| BF | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Conforming with sex-disaggregation | 18 | 40 | 35 | 27 | 33 | 30.6 |

| CF | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3.2 |

| CA | 14 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 13 | 10.2 |

| Non-conforming with sex-disaggregation | 20 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 15 | 13.4 |

| BX | 12 | 10 | 9 | 17 | 3 | 10.2 |

| CX | 12 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 9.4 |

| XX | 31 | 20 | 29 | 33 | 34 | 29.4 |

| Missing or lacking sex-disaggregation | 55 | 39 | 46 | 60 | 45 | 49.0 |

Costa Rica has the highest number of conforming and sex-disaggregated indicators. The Dominican Republic and Paraguay are close seconds. Jamaica ranks fourth, and Colombia, with only 18 conforming indicators, lags far behind. Paraguay has the largest number of missing indicators (XX), but it also has the fewest number of available indicators that lack sex-disaggregation (BX + CX). Jamaica has the smallest number of non-conforming indicators (CA+CF+CX), but it also has the second highest number of missing indicators (XX). This suggests that there may be a trade-off: publish more non-conforming indicators or adhere to standards and publish less.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of indicators available in international and national databases. The major difference between national and international databases is that the former includes more non-conforming indicators, while international databases have a higher proportion of indicators with complete disaggregation but also a larger proportion of indicators that lack sex-disaggregation. Both national and international databases have a small share of indicators that lack some specified disaggregation but include sex-disaggregation. In total, 47 percent of the possible indicators are available in national databases with sex-disaggregated data; only 45 percent are available in international databases.

Figure1: Availability of data in international and national datasets

Data timeliness and frequency

The previous tabulations counted any indicator that had at least one observation over the 10-year period, 2010 to 2019. But scattered observations are not as useful as a continuous time series, particularly for determining the trend of gender equality and the SDGs in a country, and long lags before data become available diminish their relevance. The study assessments noted the individual years for which data are available and the total number of published observations over the 10-year period.

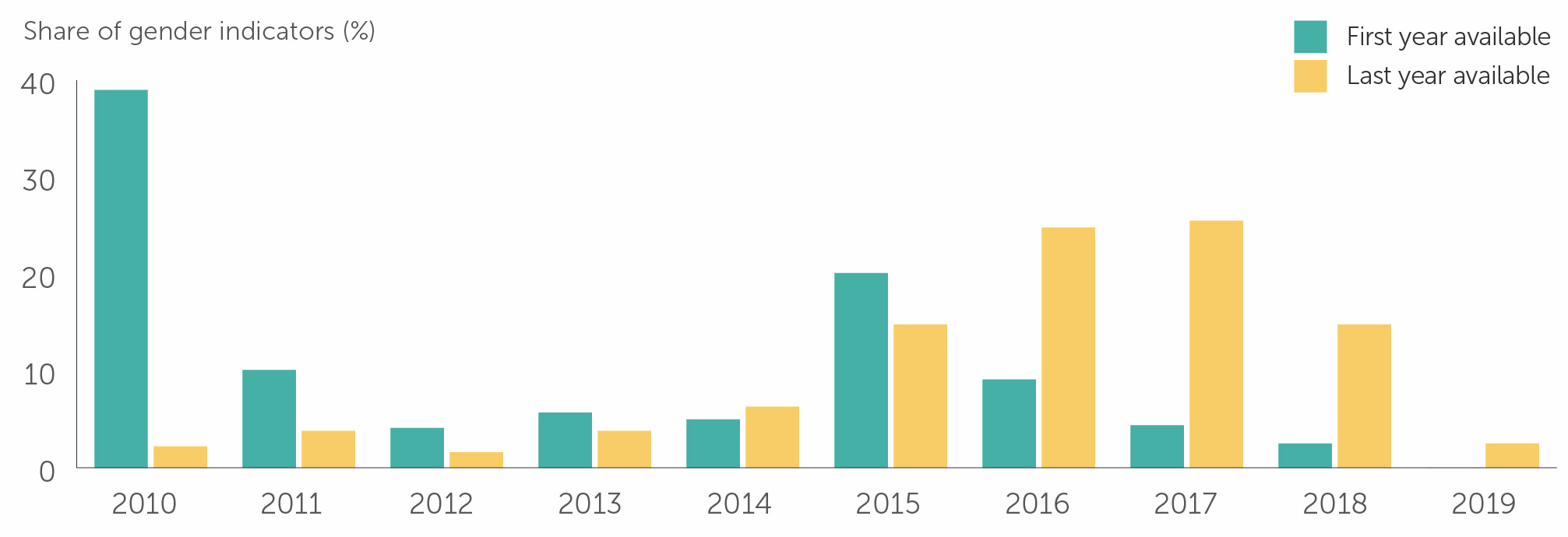

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the first and last year data are available for all 93 indicators in the national databases of the five study countries (countries with earlier data series were recorded as beginning in 2010). On average, 31.6 percent of all indicators lack any data. Of the available indicators, 39 percent have an initial observation in 2010 or earlier, but another 36 percent lack any observations before 2015. There is a pronounced surge in data availability from 2015 onwards, which may reflect the efforts to provide data at the end of the MDG period and for the baseline of the SDG period. Still, there are large lags: 32 percent of observations stop before 2016, and half of all indicators are three to four years old.

Figure 2: First and last years of data availability in national databases

Most gender indicators should be reported annually. A complete series should, therefore, include ten observations. But not all indicators are measured annually. Censuses are typically carried out once in a decade. Household surveys, collecting data on income, consumptions, and the welfare of individuals occur sporadically, but ideally every two to four years. Labor force surveys should occur annually, and administrative data, such as education data or crime statistics, are event driven but should be reported at least annually. Using standard methods for extrapolating from or interpolating between periodic data collections, annual estimates for most indicators can be produced.

Table 2 summarizes the number of observations available for all 93 indicators in national and international databases. The counts shown here are based on all available indicators, including those that lack sex-disaggregation and non-conforming indicators. In most national databases, one-third of the indicators lacked any observations over the period 2010 to 2019.

The observations of many indicators are sparse. More than half of the available indicators of the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Paraguay have three or fewer observations over the period. Costa Rica is the only country for which more than half of its national indicators have four or more observations. Paraguay is at the extreme end, having only five indicators with four or more observations in its national databases. Differences between countries are less extreme in international databases, although Jamaica falls well short of the others.

Table 2: Observations available, by country, 2010-2019

| National databases | International databases | |||||

| Indicators with no data | Indicators with 1 to 3 observations | Indicators with more than 3 observations | Indicators with no data | Indicators with 1 to 3 observations | Indicators with more than 3 observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 31 | 19 | 43 | 19 | 32 | 42 |

| Costa Rica | 20 | 24 | 49 | 27 | 26 | 40 |

| Dominican Republic | 29 | 51 | 13 | 20 | 30 | 43 |

| Jamaica | 33 | 36 | 24 | 27 | 40 | 26 |

| Paraguay | 34 | 54 | 5 | 23 | 30 | 40 |

| Five countries’ average | 29.4 | 36.8 | 26.8 | 23.2 | 31.6 | 38.2 |

The term “data frequency” suggests that indicators follow a regular schedule, published annually, biennially, or at some regular interval. Some are, but in practice, many are not. Therefore, we use the term “data density” to describe the number of observations available in a given period.

Large differences were found in the availability and density of data between indicators and between countries. For example, complete, annual data for SDG 5.5.1 (proportion of seats held by women in national parliament) were only available from the SDG Global Database or from the Interparliamentary Union. In national databases, Costa Rica published only two observations over the period 2010 to 2014, while Jamaica published seven between 2010 and 2016. This indicator is derived from administrative records of the country and should, therefore, be complete and available in national databases.

Table 3 shows the average number of observations and the range of years available. Colombia and Costa Rica have the highest data density in national databases with more than five observations on indicators with any available data. The range of years available in these countries is also greater: on average data series begin in 2011 and extend to 2016. Paraguay, with the lowest data density, lacks extended time series: over the period a typical series begins in 2015 and ends in 2016.

International databases show a more even distribution of data. Paraguay has, on average, the same number of observations and the same range of years available as Colombia and Costa Rica. The Dominican Republic also has a larger number of observations and longer time series available in international databases. Behind the averages, there are differences in the indicators available, but these results suggest that countries could make more data available simply by publishing the observations already available in international databases.

Table 3: Average indicator density and range of years, 2010-2019

| National databases | International databases | |||||

| Year 2010 – 2019 | Average number of observations per indicator with data | Average beginning year | Average final year | Average number of observations per indicator with data | Average beginning year | Average final year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 5.7 | 2011 | 2016 | 5.1 | 2012 | 2016 |

| Costa Rica | 5.5 | 2011 | 2016 | 5.0 | 2011 | 2016 |

| Dominican Republic | 2.4 | 2014 | 2015 | 5.1 | 2012 | 2016 |

| Jamaica | 3.4 | 2012 | 2015 | 3.7 | 2012 | 2015 |

| Paraguay | 2.1 | 2015 | 2016 | 5.1 | 2011 | 2016 |

| Five countries’ average | 3.9 | 2013 | 2016 | 4.7 | 2012 | 2016 |

The IAEG-SDGs classifies indicators as Tier II if they have an agreed methodology but are available in fewer than half of the countries of the world. Efforts by the custodian agencies have added methodologies to Tier III indicators since 2015, promoting them to Tier II, and the remaining indicators are expected to reach Tier II status in the coming year. Surprisingly, there is not much difference in the density or range of Tier I and Tier II indicators in the five study countries. All except Paraguay have at least one observation in their national databases on more than half the Tier II indicators. The average number of observations for Tier I indicators with data was 4.2 and for Tier II 3.6. The differences in starting and final years of Tier I and Tier II indicators are also small, always less than a year. (These averages do not include non-SDG indicators or indicators with mixed tier classifications.) The differences are larger in international databases, which adhere more strictly to the prescribed methodologies of the SDGs. The average number of observations of Tier I indicators is 5.6, but only 3.0 for Tier II indicators.

Indicator availability by development domain

As with the Bridging the Gap study in Sub-Saharan Africa, each of the 93 indicators have been classified into one of five development domains according to Buvinic et al., 2014 in addition to environment: health, education, economic opportunity, political participation and human security. Health is the largest domain with 28 indicators, followed by economy and education. The count of indicators in each domain is shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Number and share of indicators in each domain

| Domain | Number of indicators | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Economy | 20 | 21.5 |

| Education | 12 | 12.9 |

| Environment | 11 | 11.8 |

| Health | 28 | 30.1 |

| Human security | 15 | 16.1 |

| Public participation | 7 | 7.5 |

| Total | 93 | 100.0 |

The quality and availability of gender indicators differs by domain. Table 5 shows the distribution of indicators in national databases by their availability and domain across all five countries. Economic opportunity has the second highest number of gender indicators (20) and has the greatest share of conforming and sex-disaggregated indicators; health, with the largest number of indicators (28) has the third highest; political participation, with only seven indicators, ranks second. Education has the lowest share of conforming sex-disaggregated indicators, perhaps reflecting the structural differences in national educational systems. The environment domain, with the smallest proportion of available indicators also has the smallest share of indicators with sex-disaggregation. This is a gap that was also noted in the analysis of 15 Sub-Saharan African countries.

Table 5: Average availability of indicators in national databases by domain (%)

| Indicator availability | Economic Opportunity | Environment | Health | Education | Human Security | Public Participation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 29.0 | 1.8 | 21.4 | 15.0 | 10.7 | 8.6 | 17.2 |

| AF | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 3.3 | 13.3 | 20.0 | 8.2 |

| BA | 21.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 8.3 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 6.7 |

| BF | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Conforming with sex-disaggregation | 50.0 | 1.8 | 37.1 | 26.7 | 29.3 | 34.3 | 32.9 |

| CA | 9.0 | 5.5 | 11.4 | 25.0 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 11.0 |

| CF | 1.0 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 3.4 |

| Non-conforming with sex-disaggregation | 10.0 | 5.5 | 15.7 | 31.7 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 14.4 |

| BX | 5.0 | 14.5 | 18.6 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 11.0 |

| CX | 9.0 | 32.7 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 9.3 | 2.9 | 10.1 |

| XX | 26.0 | 45.5 | 22.9 | 26.7 | 41.3 | 48.6 | 31.6 |

| Missing or lacking sex-disaggregation | 40.0 | 92.7 | 47.1 | 41.7 | 58.7 | 54.3 | 52.7 |

| Key to table | |

|---|---|

| AA | Fully disaggregated data available |

| AF | Female only data with complete disaggregations |

| BA | Sex-disaggregated available lacking other disaggregations |

| BF | Female only data available lacking other disaggregations |

| BX | Available data lack sex-disaggregation |

| CA | Non-conforming data with sex-disaggregation |

| CF | Non-conforming data applicable to females only |

| CX | Non-conforming data lacking sex-disaggregation |

| XX | Not available |

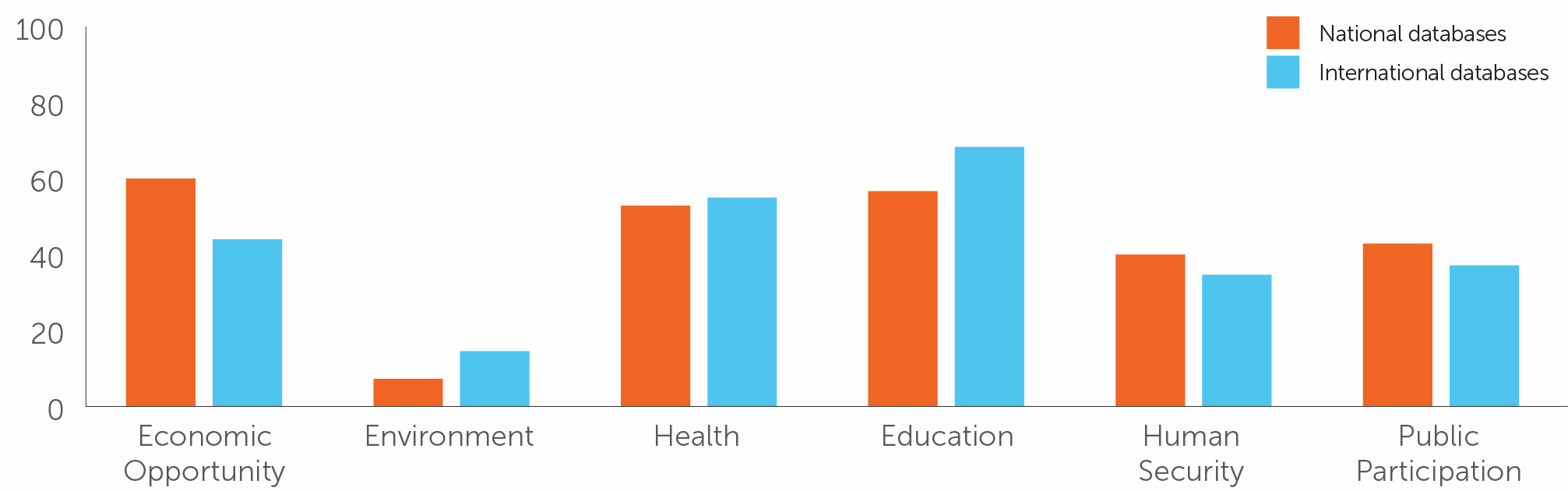

The availability of sex-disaggregated indicators in each domain differs between national and international databases. Figure 3 shows the proportion of indicators with sex-disaggregated data available. To simplify this presentation, all sex-disaggregated indicators are grouped together. The greatest difference between national and international databases occurs in the economic domain, where national databases have substantially more sex-disaggregated indicators. The smallest difference occurs in the health domain. The environment domain with only 11 gender-relevant indicators also has the smallest proportion with sex-disaggregated data and the largest relative difference between international and national databases.

Figure 3: Proportion of indicators with sex-disaggregated data by domain (%)

In the following sections we explore some of the sources of gaps and differences between national and international databases in each domain.

Economy

All the economic opportunity indicators included in this study are part of the SDG monitoring framework except the labor force participation rate. They provide an important but limited view of women’s economic roles and barriers to their full participation in the labor force. They consist primarily of measures of income or expenditures collected through household surveys and labor force indicators collected through surveys and administrative records. Other indicators measure the use of the internet by men and women and participation in the banking system. Missing from this set, however, are measures of the status of migrant women, earnings differentials, or access to childcare (Grantham, 2020).[2]

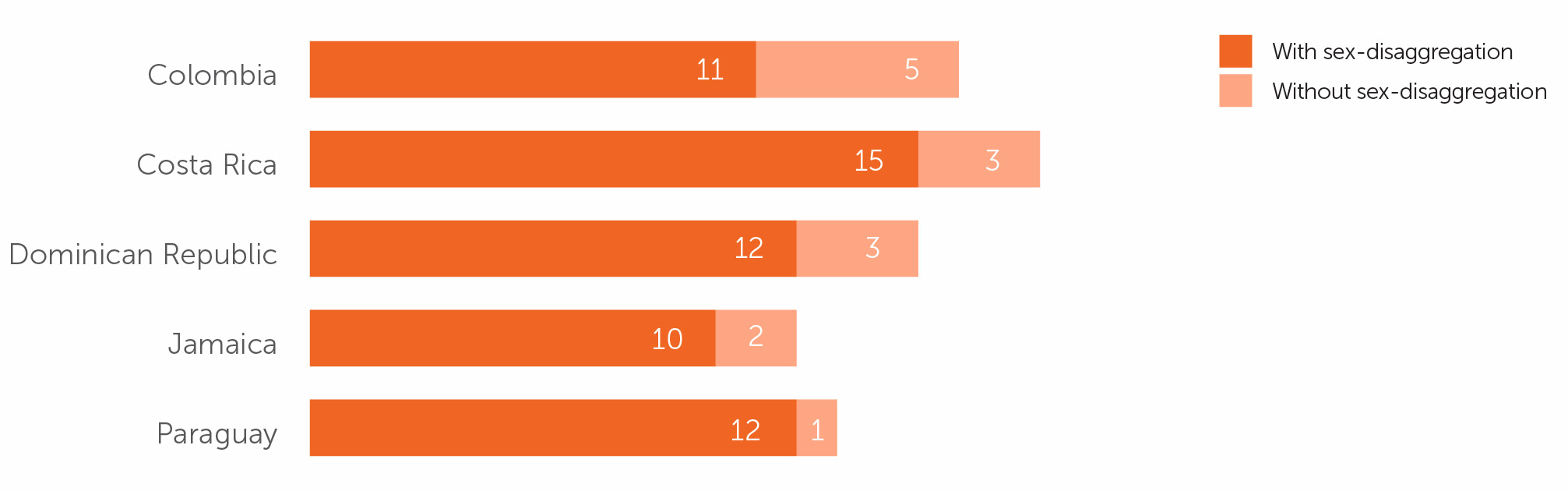

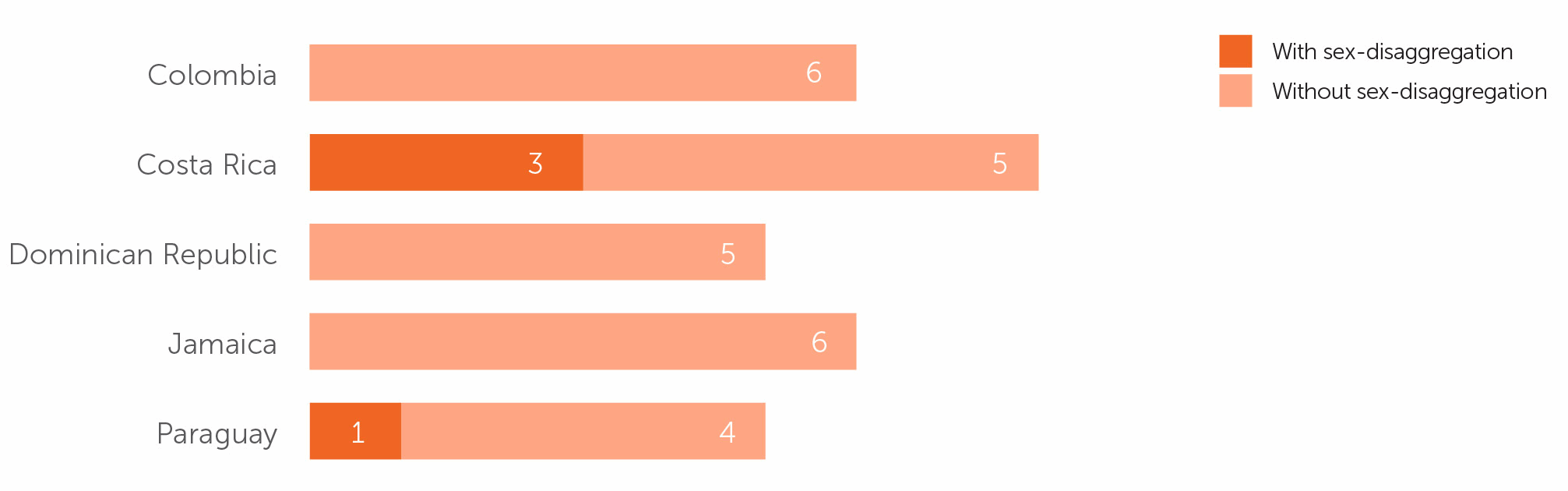

Figure 4 shows the number of indicators available in the national databases of each country. This includes both sex-disaggregated and non-disaggregated indicators for which at least one observation was available.

Figure 4: Number of economic indicators available in national databases, 2010-2019

Data collected at the household level are generally not available with sex-disaggregation because of the difficulty of assigning shared resources to individuals. Sex-disaggregated measures of poverty rates or other indicators of household income or expenditure are rarely available. An exception is the measure of the employed population below the international poverty line, the so-called working poor, calculated according to the ILO’s methodology. Three of the countries in the study reported poverty rates for men and women at the international poverty line and all five reported rates measured at national poverty lines.

Four economic indicators are unavailable with sex-disaggregation in national or international databases, including the two measures of asset ownership:

- Proportion of adults with secure tenure rights to land (1.4.2)

- Average income of small-scale indigenous producers (2.3.2)

- Proportion of total agricultural population with secure rights over agricultural land and share of women among right-bearers of agricultural land (5.a.1)

- Growth rates of household expenditure or income per capita among the bottom 40 percent of the population (10.1.1)

Four economic indicators are available with sex-disaggregation in national and international databases for all five countries:

- Unemployment rate (8.5.2)

- Labor force participation rate (not in SDGs)

- Proportion of youth not in education, employment, or training (8.6.1)

- Proportion of children engaged in child labor (8.7.1)

Of the remaining 12 economic indicators, most are available in the national databases of one or more countries, although some are produced by non-conforming methodologies. Few of these indicators are available in international databases, presenting an incomplete picture of women in the economy. The complete list of indicators and their availability is shown in Annex 1.

Education

Education measures of school enrollment, progress, and completion generally come from administrative records that are sometimes supplemented by surveys that record whether children are attending (as opposed to enrolled in) school. Measures of learning outcomes may be based on school exams, but more sophisticated measures of numeracy, literacy, or other competencies require specialized assessments. Measures of the facilities, learning materials, and teaching staff are also of importance for the quality of education . The SDGs include only one gendered facility indicator: the availability of single-sex sanitation facilities.

Figure 5 shows the number of education indicators available in the national databases of each country. These include both sex-disaggregated and non-disaggregated indicators. No country has a complete set of education indicators (12), but Jamaica and Paraguay come closest. Jamaica lacks data for two supplemental (non-SDG indicators): proportion of women with six or fewer years of education and proportion of women with less than a high school diploma. Paraguay lacks data for proportion of women with less than a high school diploma and SDG indicator 4.c.1, the proportion of teachers with appropriate qualifications at each school stage.

Figure 5: Education indicators in national databases, 2010-2019

Because these indicators reflect the structure of national (or local) education systems and national standards for educational achievement, they may not conform to international standards. As a result, in the five study countries, 24 out of 35 indicators with sex-disaggregated data are classified as non-conforming. In the international databases, 12 observations rely on non-conforming indicators but only a total of 24 observations are available out of a possible 60.

The assessment results show a mixed pattern. Only literacy and numeracy rates (4.6.1) are available in the national databases of all five countries, four of which were classified as non-conforming. Only a single instance of the indicator was found (without sex-disaggregation) in international databases. This may reflect reporting problems or the rejection of non-conforming indicators by international compilers.

Environment

Environment indicators in this study were selected because their data could plausibly be disaggregated by sex. All of them deal with the built environment: adequacy of housing, access to water, sanitation, and transportation services, and exposure to indoor pollution and natural disasters. This is not to say that the condition of the natural environment does not have a differential impact on men and women; however, indicators of resource use or environmental degradation are not measurable with sex-disaggregation. UN Women has suggested some supplemental indicators for the environmental goals (UN Women, 2018) that capture women’s activities, such as the proportion of women and men working in fisheries or sex-disaggregated statistics on household fuel collection and forest conservation activities. These indicators were not included in the study set because they lack an agreed methodology.

No environment indicator is available in all countries. As shown in Figure 6, even including indicators without sex-disaggregation, many countries lack any data for many of the 11 environment indicators.

Figure 6: Environment indicators available in national databases, 2010-2019

The environment is the domain with least availability of sex-disaggregated indicators. Seven indicators are unavailable or lack sex-disaggregation in either national or international databases:

- Number of deaths, missing persons, and directly affected persons attributed to disasters (1.4.1)

- Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services (6.1.1)

- Proportion of population using safely managed sanitation services, including a hand-washing facility with soap and water (6.2.1)

- Proportion of the rural population who live within two km of an all-season road (9.1.1)

- Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements, or inadequate housing (11.1.1)

- Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age, and persons with disabilities (11.2.1)

- Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age, and persons with disabilities (11.7.1)

Many of the indicators identified as being capable of sex-disaggregation are collective goods, facilities, or services shared by all household members. Like other indicators recorded at the household level, it is difficult to differentiate access or use by individuals. However, it is still possible to calculate the proportion of women living in households that share or have access to the facility or service. Similarly, surveys or administrative data that include the age or disability status of household members could be used to provide average measures.

Health

The SDGs include 25 indicators of women’s health spread across five goals. They fall into three broad groups: measures of undernourishment or food insecurity, including stunting in children; measures of disease incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates of mothers and children; and measures of reproductive health and agency. We included three supplemental indicators recommended by UN Women for a total of 28, of which 18 are included in Goal 3 (“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”). The others fall under Goals 2, 4, 5, and 8. Eight of the 28 health indicators are specific to women; the remaining 20 apply to both males and females.

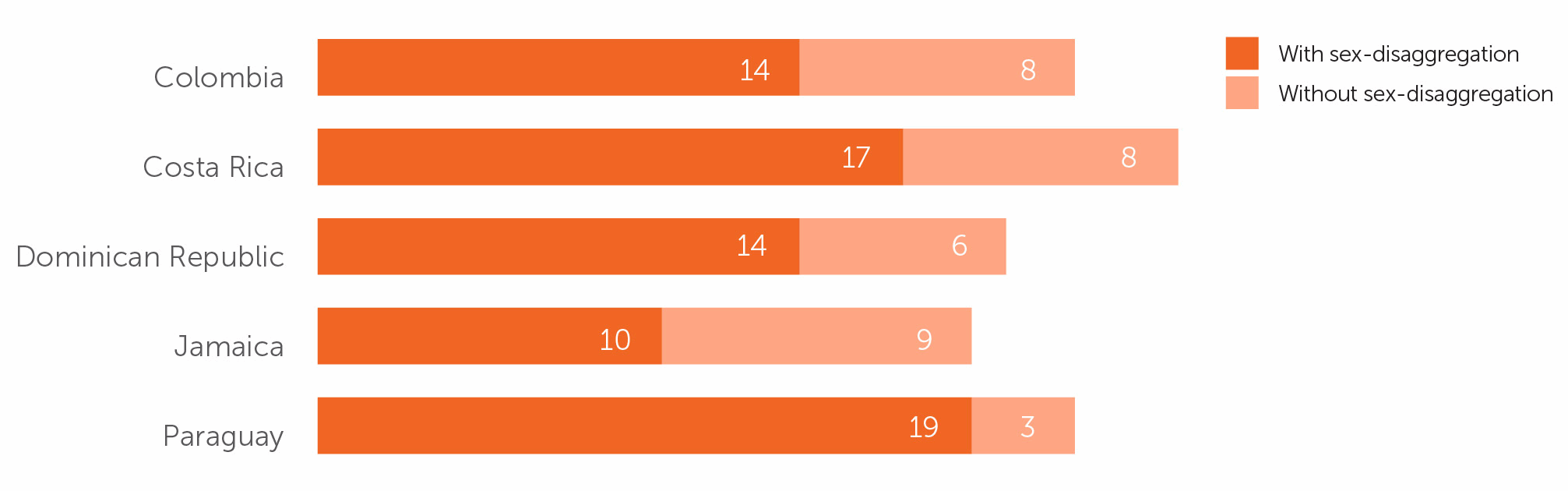

As shown in figure 7, Costa Rica’s national databases provide at least one observation on 25 indicators, although this includes eight that lack sex-disaggregation. Paraguay with 22 indicators with data has only three that lack sex-disaggregation.

Figure 7: Health indicators available in national databases, 2010-2019

Three health indicators were unavailable or lacked sex-disaggregation in national or international databases of the five study countries:

- Malaria incidence

- Hepatitis B incidence

- Number of people requiring interventions against neglected tropical diseases

These indicators are generally available in the SDG Global Database for other countries from the region, although without sex-disaggregation.

Also missing from national databases was the frequency rate of occupation injuries, and from international databases, five more indicators were unavailable or lacked sex-disaggregation:

- Children under five years of age who are developmentally on track in health, learning, and psychosocial well-being

- Women aged 15-49 years who make their own informed decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use, and reproductive health care

- Prevalence of undernourishment

- Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity

- Proportion of the target population covered by all vaccines included in their national programme

For each of these indicators, only one or two countries could provide data in their national databases. Nevertheless, the lack of data at the international level is surprising and points to gaps in the global programs for data collection and dissemination.

There were five health indicators with data in national and international databases for all five countries:

- Prevalence of malnutrition among children under five years of age

- Maternal mortality ratio

- Under-five mortality ratio

- Suicide mortality rate

- Adolescent birth rate

Human security

There are 15 human security indicators, the majority of which record experience of violence or perceptions of danger. Eleven fall under SDG 16 (“Peaceful and inclusive societies…”) along with four from Goal 5 (“Gender equality”) that refer specifically to women and girls. Data for these indicators, particularly those concerning sexual violence, are difficult to collect, requiring carefully planned and administered individual survey — though administrative records, such as police reports, are usually incomplete or unreliable.

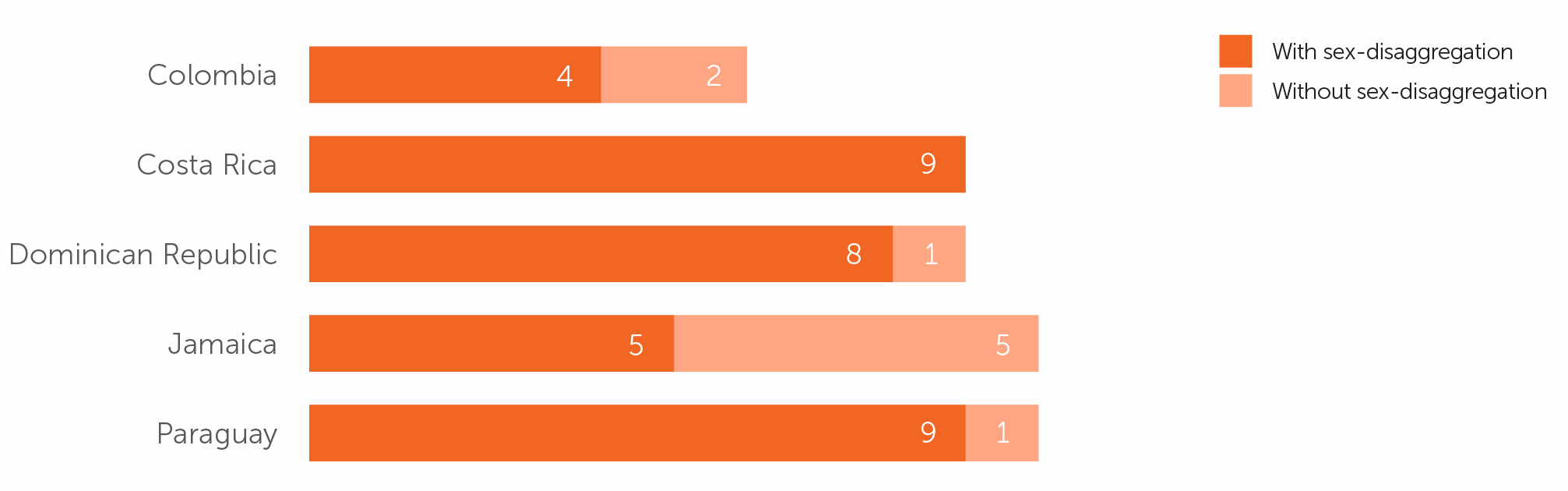

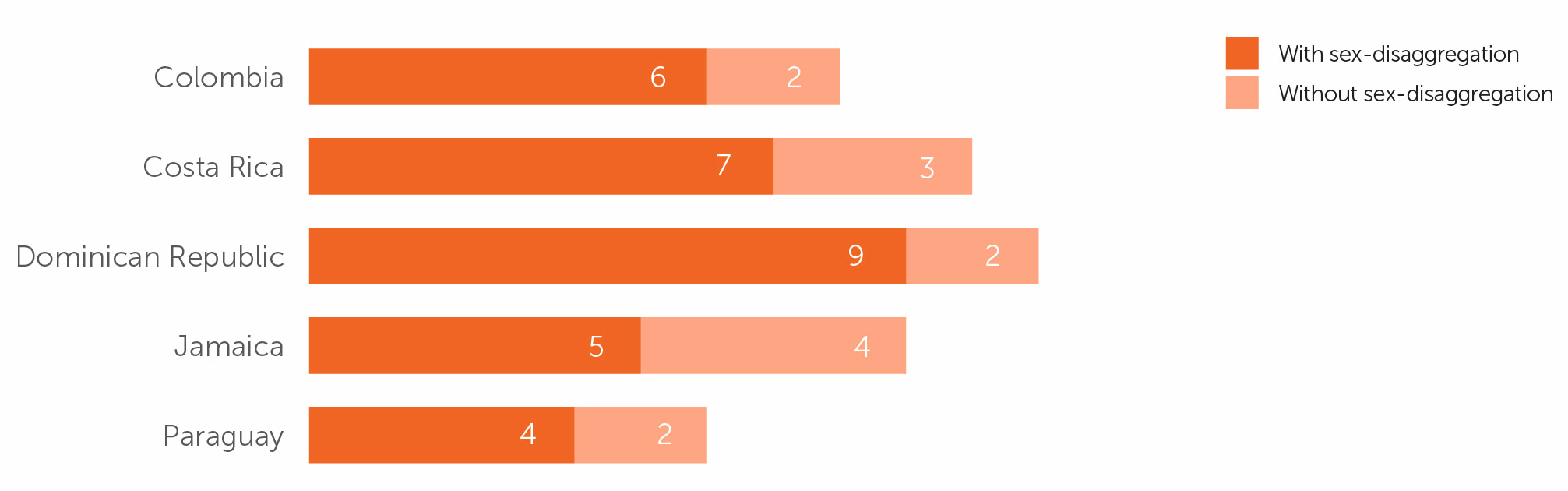

As shown in Figure 8, the Dominican Republic has the most complete set of human security indicators, of which nine are available with sex-disaggregation. Paraguay, with six out of 15 indicators, reports sex-disaggregated data for only four.

Figure 8: Human security indicators available in national databases, 2010-2019

Three indicators are not available with sex-disaggregation in either national or international databases:

- Girls and women who have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) or cutting (5.3.2)

- People who report having felt personally discriminated against or harassed (16.b.1/10.3.1)

- Conflict-related deaths (16.1.2)

FGM is not commonly practiced in the region, although there are reports of its occurrence in parts of Colombia.[3] Indicator 16.b.1, meanwhile, was originally classified as Tier III and has been upgraded to Tier II. The methodology calls for a survey module with two questions about 12 possible grounds for discrimination. No record exists of such a survey being carried out in the study countries. The methodology for collecting indicator 16.1.2 recognizes that there are multiple possible data sources and differences in the definition of conflict-related deaths. It is classified as Tier II, indicating that data are not widely available, but it is still noteworthy that Colombia, which was engaged in a prolonged civil war until recently, has no data.

Two indicators are available with sex-disaggregation in national and international databases for all countries:

- Women aged 20–24 years who were married or in union before age 15 and age 18 (5.3.1)

- Victims of intentional homicide (16.1.1)

Data on homicides are the most available crime statistics because homicide is a crime that is generally reported, while other crimes against persons or property are generally believed to be underreported by victims or by police or other authorities.

Public participation

Public participation is the smallest domain, with only seven gender indicators, all included in the SDGs. Three of these indicators concern the proportion of women holding high positions in government, business, and other public institutions. Two record contact with public services. Perhaps the most immediately relevant to improving the quality of gender statistics is the proportion of children who have been registered with a civil authority.

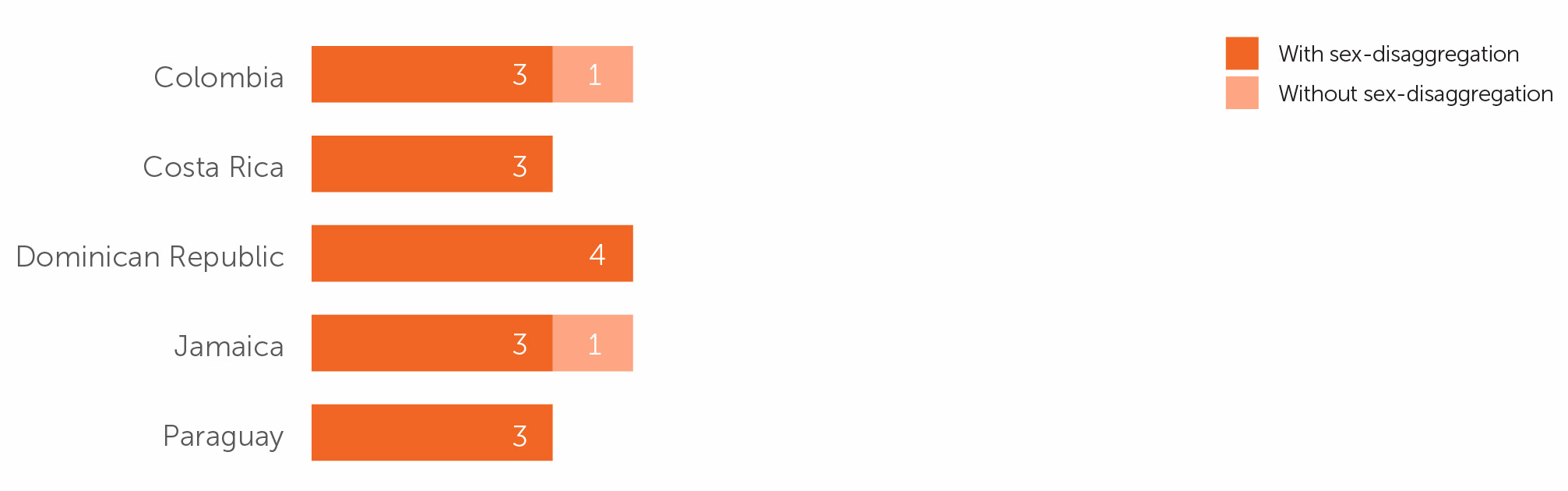

Figure 9: Public participation indicators available in national databases, 2010-2019

Figure 9 shows that only the Dominican Republic has more than three sex-disaggregated indicators in its national database. The most widely reported indicator is the proportion of seats held in parliament which is available for every country and is regularly reported by the Interparliamentary Union. However, no country provides similar data for legislative or executive positions in local governments.

Two indicators have recently been upgraded to Tier II but remain unavailable with sex-disaggregation in national or international databases. They will need to be incorporated into appropriate surveys. Both ask for the subjective opinions of respondents:

- Proportion of population satisfied with their last experience of public services (16.6.2)

- Proportion of population who believe decision-making is inclusive and responsive (16.7.2)

Data and gender policies

As already established, data is critical for measuring and monitoring progress toward achieving national and global goals for gender equality and women’s autonomy. To be most effective, these data must be incorporated in decision-making processes and government policies.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, different strategies and public policies have been adopted to address the data gaps in measuring and addressing gender inequality. These include national equality plans containing strategic objectives and goals for strengthening gender equality and increasing women’s autonomy. Moreover, in response to the recommendations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women for the establishment of accountability mechanisms for the monitoring and evaluation of the implementation and impacts of these policies and plans, countries such as Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and Paraguay have evaluated their national equality policies and plans in recent years (ECLAC, 2019b).

At the regional level, the Montevideo Strategy for Implementation of the Regional Gender Agenda within the Sustainable Development Framework by 2030 (ECLAC, 2016) has become a guide for directing the design of gender equality plans and policies. It is a political-technical instrument adopted in 2016 by the member States of ECLAC at the thirteenth session of the Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean — with the aim of advancing the implementation of the Regional Gender Agenda, and ensuring that it serves as a road map for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the regional level, from the perspective of gender equality and women’s autonomy and human rights.

One of the ten implementation pillars set under this strategy concerns the strengthening of information systems, with the aim of “transforming data into information, information into knowledge, and knowledge into political decision.” It proposes nine measures to establish and strengthen national statistical systems with a gender perspective, including disaggregation and dissemination of data by sex, age, race and ethnic origin, socioeconomic status, and area of residence, in order to improve analyses to reflect the diversity of women’s situations. It recommends developing and strengthening instruments such as surveys on time use, violence against women, sexual and reproductive health, and use of public spaces to better measure gender inequalities. It also recommends building and strengthening institutional partnerships between bodies that produce and use information, particularly between entities for the advancement of women, national statistical offices, academic institutions, and national human rights institutions, along with the Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean and the Statistical Conference of the Americas of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2016).

One of the most significant advances made in recent years in the region is the importance that has been placed on the production of statistics with a gender perspective. With regards to the application of the Montevideo Strategy on information systems, the region’s countries have reported initiatives that include the construction of repositories, the strengthening of administrative records and the creation of information systems, gender observatories, and atlases. Of particular note are the advances made in measuring time use and the distribution of unpaid work and in the conceptual and methodological development of methods to quantify femicide (ECLAC, 2019a).

This is reflected in the priority that the Latin American and Caribbean countries have placed on the regional set of indicators for monitoring the region’s progress toward the SDGs within the framework of the Statistical Conference of the Americas of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (SCA), which includes two gender-related indicators that did not originally feature in the framework of global indicators — total work time and the femicide rate — but were part of the Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2018b).

This can be seen as a culmination of the intergovernmental efforts made in the region, for instance, the important role played by the Working Group of Gender Statistics (WGGS) of the SCA of ECLAC, which was approved by the Fourth Conference of the SCA in 2007. This working group, coordinated by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), has been working towards aligning the requirements of the countries in the region with the SDGs, to formulate ways of developing capacities and the strengthening of methodologies for the production and use of data, as well as the development of gender indicators related to human rights and the advancement of women and girls on issues such as poverty, access to technology, women’s participation in decision-making, time use and work, statistics, and violence against women and girls, among others (ECLAC, 2006).

Furthermore, recognizing the cross-cutting nature of gender issues, Resolution 11(X) adopted at the tenth meeting of the Statistical Conference of the Americas of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, held in 2019, in Article 26 asks “that the working groups of the Statistical Conference of the Americas mainstream the gender perspective into their work, along with other cross-cutting elements of statistical work such as classifiers.” (ECLAC, 2019c) In the following section, we examine the data required to implement and monitor gender policies in the selected countries through an examination of their recent national plans.

Colombia

The National Development Plan (NDP) 2018-2022 titled, “Pact for Colombia, Pact for Equity” (Pacto por Colombia, pacto por la equidad) addresses cross-cutting themes including gender equality; environmental sustainability; science, technology and innovation; transport and logistics; digital transformation; public services in water and energy; mining resources; identity and creativity; peace building; ethnic groups; and people with disabilities (DNP, 2018). While the plan was designed with targets aligned with the national vision as well as the commitments towards the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, the SDGs have served as a tool for promoting coherence within and between the different sections of the plan.

The importance of monitoring gender gaps has also received support high-level support. Colombia has launched the Colombian Women’s Observatory, regulated by Law 1009 of 2006, which endorsed the responsibility to the Administrative Department of the Presidency of the Republic, through the Presidential Counseling for Women’s Equity. This Observatory aims to collect, analyze and disseminate information related to the situation of women living in Colombian territories, as well as to support the formulation and monitoring of public policies to close gender equity gaps in Colombia, at the national, regional and local levels (Colombian Women’s Observatory, n.d.).

Previously, the Government of Colombia’s National Council for Economic and Social Policy implemented the National Policy for Gender Equality 2013-2016 (CONPES, 2013). While the national policy had clearly defined objectives, the plan did not set any measurable targets to monitor these objectives. Because the national policy was introduced prior to the adoption of Agenda 2030, it did not align with the goals and frameworks of the SDGs.

The new plan represents the first time in the country’s history that a dedicated crosscutting “Pact for Women’s Equity” has been incorporated in the national development plan, including measures to promote women’s autonomy in physical, economic, political, and educational dimensions (ECLAC, 2019a).

-