Parenting in America

3. Parenting approaches and concerns

American parents across demographic groups say being a parent is central to who they are, but the ways they approach parenting – and the concerns they have about their children – vary in some significant ways between mothers and fathers as well as across generations, and racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

American parents across demographic groups say being a parent is central to who they are, but the ways they approach parenting – and the concerns they have about their children – vary in some significant ways between mothers and fathers as well as across generations, and racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

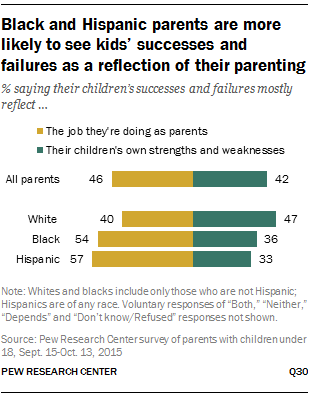

For example, while similar shares of black and white parents say it is extremely important to them for their children to grow up to be honest and ethical and caring and compassionate, black parents place more value than white parents on raising their kids to be hardworking, ambitious and financially independent. Black parents, as well as those who are Hispanic, are also more likely than white parents to say their children’s successes and failures mostly reflect the job they’re doing as parents, while whites are more likely to say this mostly reflects their children’s own strengths and weakness.

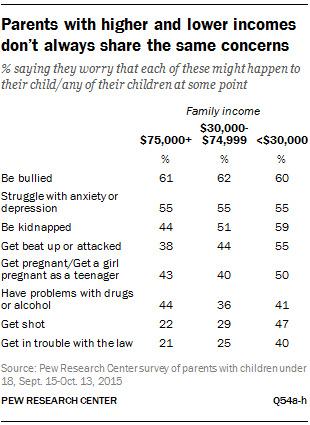

When it comes to concerns about challenges their children may face, bullying and mental health issues such as anxiety and depression top the list. But for black and Hispanic parents, as well as for those with lower incomes, the fear that their child or one of their children might get shot at some point is relatively common. And among parents with annual family incomes of less than $30,000, concerns about teenage pregnancy, physical attacks and their kids getting in trouble with the law are also more prevalent than among those who earn $75,000 or more.

This chapter explores the parenting styles and philosophies of parents across demographic groups, as well as their concerns and aspirations for their children’s future.

Parenting styles differ between mothers and fathers

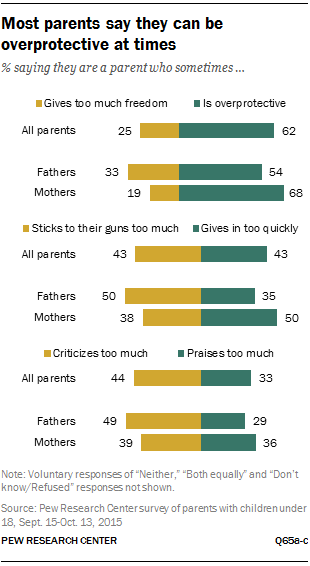

A majority of American parents (62%) say they can sometimes be overprotective, and this is particularly the case among mothers. Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) moms describe themselves this way, compared with 54% of dads. About one-in-five (19%) moms and a third of dads say they are the type of parent who sometimes gives too much freedom.

A majority of American parents (62%) say they can sometimes be overprotective, and this is particularly the case among mothers. Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) moms describe themselves this way, compared with 54% of dads. About one-in-five (19%) moms and a third of dads say they are the type of parent who sometimes gives too much freedom.

Mothers are also more likely than fathers to describe themselves as a parent who sometimes gives in too quickly. Overall, the same share of parents say they give in too quickly as say they stick to their guns too much (43% each). Among moms, half say they sometimes give in too quickly, while 38% say they sometimes stick to their guns too much. Dads’ answers are nearly the mirror opposite: half say they sometimes stick to their guns too much, while 35% say they sometimes give in too quickly.

Mothers and fathers also describe themselves differently when asked if they are the type of parent who criticizes or praises too much. Among all parents, somewhat more say they criticize too much (44%) than praise too much (33%), and this is especially the case among dads. About half (49%) of dads say they sometimes criticize their kids too much, while 29% say they sometimes offer too much praise. Among moms, about an equal share say they sometimes are too critical (39%) as say they sometimes praise their kids too much (36%).

Millennials more likely to say they sometimes give too much praise

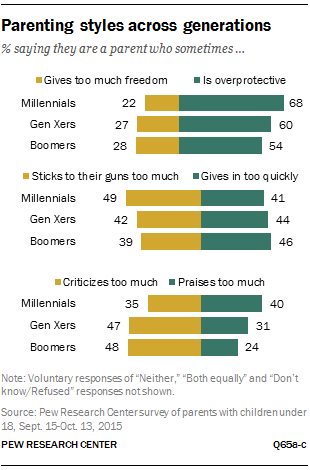

Millennials and older parents describe their parenting styles in different ways, but these differences can be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that Millennials tend to have younger children. For example, about two-thirds (68%) of Millennial parents say they can sometimes be overprotective, compared with 60% of Gen X and 54% of Boomer parents. But when looking only at parents who have children younger than 6, about an equal share of Millennials (71%) and older parents (65%) say they can sometimes be overprotective. Similarly, while Millennials are more likely than older parents to say they sometimes stick to their guns too much when it comes to their children, the difference virtually disappears when only those with young children are considered.

Millennials and older parents describe their parenting styles in different ways, but these differences can be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that Millennials tend to have younger children. For example, about two-thirds (68%) of Millennial parents say they can sometimes be overprotective, compared with 60% of Gen X and 54% of Boomer parents. But when looking only at parents who have children younger than 6, about an equal share of Millennials (71%) and older parents (65%) say they can sometimes be overprotective. Similarly, while Millennials are more likely than older parents to say they sometimes stick to their guns too much when it comes to their children, the difference virtually disappears when only those with young children are considered.

Yet, there is one area in which Millennials stand out, even when looking only at parents with children younger than 6: Millennials are more likely than Gex X or Boomer parents to describe themselves as parents who can sometimes praise too much. Four-in-ten Millennials say this, while 35% say they can sometimes criticize too much. In contrast, about half of Gen X and Boomer parents say they sometimes criticize too much (47% and 48%, respectively), while 31% of Gen Xers and 24% of Boomers say they sometimes give too much praise.

Other demographic differences in parenting styles also stand out. For example, college-educated parents are more likely than those who did not attend college to say they sometimes criticize their kids too much; half of parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher and 45% of those with some college describe themselves this way, compared with 36% of parents with a high school diploma or less.

Across racial and ethnic groups, Hispanics are more likely than white or black parents to say they sometimes praise their kids too much; 42% of Hispanic parents say this, compared with about three-in-ten white (30%) and black (31%) parents. When it comes to describing themselves as overprotective, about seven-in-ten black (70%) and Hispanic (72%) parents do so, compared with a narrower majority of white parents (57%). And black parents (54%) are more likely than white (43%) and Hispanic (41%) parents to say they sometimes stick to their guns too much when it comes to parenting.

Many parents say their kids’ successes and failures reflect parenting

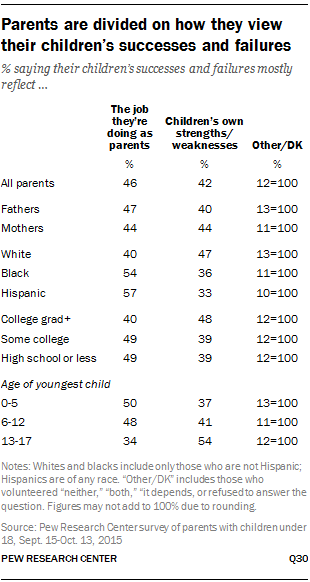

American parents are quite divided on how much responsibility they bear for the happy victories and inevitable defeats their children face as they grow up. For some (46%), their children’s successes and failures reflect, for the most part, the job they’re doing as parents. But about an equal share (42%) say these ups and downs mostly reflect their children’s own strengths and weaknesses. Fathers are somewhat more likely to say their children’s successes and failure mostly reflect the job they’re doing as parents (47%) than they are to say they reflect the kids’ own strengths and weaknesses (40%). Moms are evenly divided: 44% give each answer.

American parents are quite divided on how much responsibility they bear for the happy victories and inevitable defeats their children face as they grow up. For some (46%), their children’s successes and failures reflect, for the most part, the job they’re doing as parents. But about an equal share (42%) say these ups and downs mostly reflect their children’s own strengths and weaknesses. Fathers are somewhat more likely to say their children’s successes and failure mostly reflect the job they’re doing as parents (47%) than they are to say they reflect the kids’ own strengths and weaknesses (40%). Moms are evenly divided: 44% give each answer.

There are also some modest differences by race. Among whites, about half (47%) say their kids’ successes and failures are mostly a reflection of the children’s own strengths or weaknesses, while somewhat fewer (40%) say it mostly reflects the job they’re doing as parents. Among black and Hispanic parents, however, narrow majorities (54% and 57%, respectively) say their children’s successes and failures are mostly a reflection of the job they’re doing as parents.

There are also some differences across education groups. Among parents who have a bachelor’s degree, more say their children’s successes and failures mostly reflect their children’s own strengths and weaknesses (48%) than say this mostly reflects the job they are doing as parents (40%). The opposite is true among those with some college or with a high school diploma or less.

In some ways, views on whether the responsibility lies more with the parent or the child depend on the age of the child. In particular, parents of teenagers are far more likely than parents with younger children to give their offspring the credit, or the blame. About half (54%) of parents whose youngest child is between ages 13 and 17 say their children’s successes and failures mostly reflect their children’s own strengths and weakness, compared with about four-in-ten for parents whose youngest child is 12 or under.

One-in-six use spanking as discipline at least sometimes

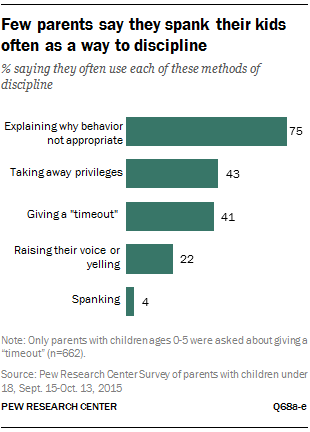

American parents employ many methods of discipline with their children, but explaining why their behavior wasn’t appropriate is the one used most frequently: three-quarters of parents say they do this often, while about four-in-ten say they often take away privileges (43%) or give a “timeout” (41% of parents with kids younger than 6). About one-in-five (22%) parents say they often raise their voice or yell at their kids, and 4% say they turn to spanking often as a way to discipline their kids.

American parents employ many methods of discipline with their children, but explaining why their behavior wasn’t appropriate is the one used most frequently: three-quarters of parents say they do this often, while about four-in-ten say they often take away privileges (43%) or give a “timeout” (41% of parents with kids younger than 6). About one-in-five (22%) parents say they often raise their voice or yell at their kids, and 4% say they turn to spanking often as a way to discipline their kids.

With the exception of spanking, mothers are more likely than fathers to say they rely on each method of discipline often. For example, nearly half (47%) of moms say they often take away privileges, compared with 39% of dads who say the same. And while majorities of mothers and father say they often discipline by explaining to their kids why their behavior was inappropriate, more moms than dads say they do this (80% vs. 70%). An equal share of moms and dads (4% each) say they often spank their children when they need to be disciplined.

While few parents say they frequently rely on spanking, more than four-in-ten (45%) have used this method of discipline with their children, with 17% saying they use it at least some of the time and 28% who rarely spank; 53% say they never spank their children. Black parents are more likely than white or Hispanic parents to say they give spankings at least some of the time: one-third say this, compared with 14% of white parents and 19% of Hispanic parents. And while at least half of white (55%) and Hispanic (58%) parents say they never rely on spanking as a form of discipline, far fewer black parents (31%) say this.

Spanking is also correlated with educational attainment: Parents with a post-graduate degree are less likely than those with a college degree or less education to say they spank their children at least some of the time. Some 8% among the most educated parents say this is the case, compared with 15% of college graduates who did not obtain a post-graduate degree, 18% of those with some college experience, and 22% of those with a high school diploma or less. Among parents with a post-graduate degree, 64% say they never spank, compared with about half of those with less education.

For the most part, reliance on other methods of discipline does not vary as much across demographic groups, but white parents with children younger than 6 are more likely than black and Hispanic parents with children in the same age group to say they often give “timeouts” as a form of discipline (50% vs. 33% and 27%, respectively). And while roughly eight-in-ten among those with at least some college say they often explain to their children why their behavior was inappropriate, about six-in-ten of those with a high school diploma or less say they do this often.

Parents want to raise honest, compassionate and hardworking kids

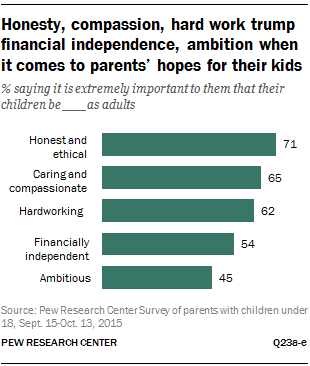

About seven-in-ten (71%) American parents say it is extremely important to them that their children be honest and ethical as adults, and at least six-in-ten place the same importance on having kids who grow up to be caring and compassionate (65%) and hardworking (62%).

About seven-in-ten (71%) American parents say it is extremely important to them that their children be honest and ethical as adults, and at least six-in-ten place the same importance on having kids who grow up to be caring and compassionate (65%) and hardworking (62%).

Financial independence is seen as extremely important by a narrower majority (54%) of American parents, while fewer than half (45%) say it is extremely important to them that their children be ambitious as adults.

About the same shares of white and black parents say it is extremely important to them for their children to be honest and ethical and caring and compassionate as adults. But, by double digits, black parents are more likely than white parents to hope their children grow up to be hardworking (72% vs. 62%), financially independent (67% vs. 53%) and ambitious (60% vs. 46%). Hispanic parents are less likely than white or black parents to say they consider each of the five items tested an extremely important trait for their children to have as adults.

Higher-income parents are more likely than those with lower incomes to say it is extremely important to them that their children grow up to be honest and ethical, but majorities across income groups say this (79% among those with annual family incomes of $75,000 or higher, 70% with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999, and 63% with incomes less than $30,000). About two-thirds or more of parents in the higher-income group say it is extremely important for their kids to be caring and compassionate (71%) and hardworking (66%) as adults. Among those in the lower-income group, about six-in-ten say both of these traits are extremely important (57% and 58%, respectively).

For the most part, there are no generational differences in the traits parents value most, but Millennial parents are more likely than older parents to say it is extremely important to them that their kids grow up to be ambitious. About half (52%) of Millennial parents say this, compared with about four-in-ten Gen X (43%) and Boomer (40%) parents.

About four-in-ten place high value on college degree

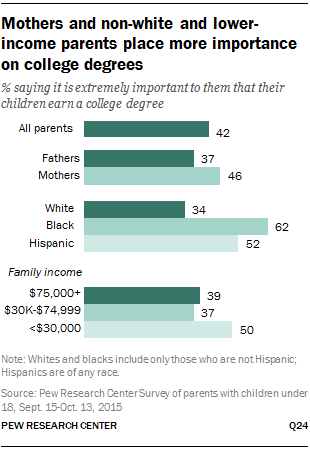

About four-in-ten (42%) parents say it is extremely important to them that their children earn a college degree, and an additional 31% say this is very important to them. Mothers are more likely than fathers to say a college degree is extremely important (46% vs. 37%).

About four-in-ten (42%) parents say it is extremely important to them that their children earn a college degree, and an additional 31% say this is very important to them. Mothers are more likely than fathers to say a college degree is extremely important (46% vs. 37%).

Black and Hispanic parents are more likely than white parents to say it is extremely important to them that their children earn a college degree; about six-in-ten (62%) African American and 52% of Hispanic parents say this, compared with about a third (34%) of white parents.

Parents with lower incomes are also more likely than those with higher incomes to value a college degree. Half of parents with an annual family income below $30,000 say it is extremely important to them that their children graduate from college, compared with about four-in-ten of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (37%) and those with incomes of $75,000 or higher (39%).

The relationship between having a college degree and seeing it as essential to one’s child is not as clear. While parents who have a bachelor’s degree are more likely than those with some college to say it is extremely important to them that their children earn a college degree (46% vs. 36%), they are no more likely than those with a high school diploma or less (42%) to say this is the case.

Bullying tops list of parents’ concerns

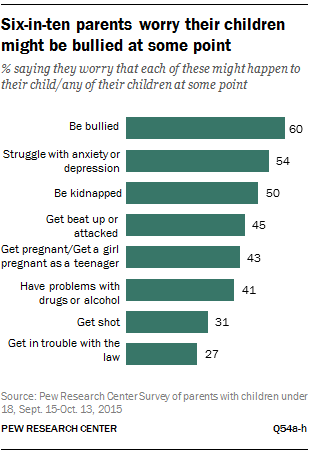

Six-in-ten parents worry that their child or any of their children might be bullied at some point, and at least half also worry that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression (54%) or that they might be kidnapped (50%). About four-in-ten parents express concerns about their children getting beat up or attacked (45%), getting pregnant or getting a girl pregnant as a teenager (43%) and having problems with drugs or alcohol (41%).

Six-in-ten parents worry that their child or any of their children might be bullied at some point, and at least half also worry that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression (54%) or that they might be kidnapped (50%). About four-in-ten parents express concerns about their children getting beat up or attacked (45%), getting pregnant or getting a girl pregnant as a teenager (43%) and having problems with drugs or alcohol (41%).

Smaller but substantial shares of parents worry that their children might get shot at some point; about three-in-ten (31%) say this is a concern. And about a quarter (27%) worry their children might get in trouble with the law.

Mothers are particularly concerned about bullying, mental health, and kidnappings. About two-thirds (65%) of mothers worry that their child or children might be bullied at some point, compared with 55% of fathers who worry about this. Similarly, mothers are more likely than fathers to say they worry that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression (57% vs. 51%) and that their kids might be kidnapped (55% vs. 44%).

Parental concerns vary across income groups, with those with an annual family income below $30,000 far more likely than those with incomes of $75,000 or higher to worry about violence, teenage pregnancy and legal trouble for their kids. For example, 55% of lower-income parents worry that their children might be beat up or attacked, and 47% worry they might get shot at some point. Among those in the high income group, 38% worry about their children being physically attacked, while about a one-in-five (22%) are concerned about gun violence.

Parental concerns vary across income groups, with those with an annual family income below $30,000 far more likely than those with incomes of $75,000 or higher to worry about violence, teenage pregnancy and legal trouble for their kids. For example, 55% of lower-income parents worry that their children might be beat up or attacked, and 47% worry they might get shot at some point. Among those in the high income group, 38% worry about their children being physically attacked, while about a one-in-five (22%) are concerned about gun violence.

Similarly, more parents with family incomes below $30,000 (50%) than those with incomes of $75,000 or higher (43%) worry that their child or children might get pregnant or get a girl pregnant as a teenager. And those with low incomes are about twice as likely as those with high incomes to say they worry their kids might get in trouble with the law at some point (40% vs. 21%, respectively).

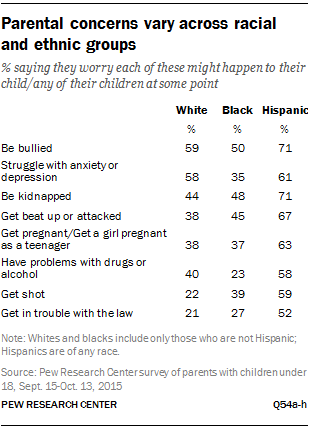

There are also some differences in the concerns expressed by parents across different racial and ethnic backgrounds. In particular white parents are far more likely than black parents to worry that their kids might struggle with anxiety or depression (58% vs. 35%) or that they might have problems with drugs or alcohol (40% vs. 23%). Black parents, in turn, are more likely to worry their kids might get shot at some point. About four-in-ten (39%) black parents say this is a concern, compared with about one-in-five (22%) white parents, and this difference persists even when looking only at white and black parents who live in urban areas, where there is more concern about shootings. Overall, 40% of all parents in urban areas worry that their child or children might get shot, compared with 29% of parents in the suburbs and 21% of parents in rural parts of the country.

There are also some differences in the concerns expressed by parents across different racial and ethnic backgrounds. In particular white parents are far more likely than black parents to worry that their kids might struggle with anxiety or depression (58% vs. 35%) or that they might have problems with drugs or alcohol (40% vs. 23%). Black parents, in turn, are more likely to worry their kids might get shot at some point. About four-in-ten (39%) black parents say this is a concern, compared with about one-in-five (22%) white parents, and this difference persists even when looking only at white and black parents who live in urban areas, where there is more concern about shootings. Overall, 40% of all parents in urban areas worry that their child or children might get shot, compared with 29% of parents in the suburbs and 21% of parents in rural parts of the country.

On nearly all items tested, Hispanic parents are more likely than white or black to express concern. By double digits, more Hispanic than black or white parents say they worry that their child or children might be bullied, be kidnapped, get beat up or attacked, get pregnant or get a girl pregnant as teenager, have problems with alcohol, get shot, and get in trouble with the law. Hispanic parents are about as likely as white parents – and far more likely than black parents – to worry about their kids struggling with anxiety or depression.

Concerns about bullying and kidnappings are especially prevalent among parents with kids younger than 13. At least six-in-ten parents whose only or youngest child is younger than 6 (66%) or between ages 6 and 12 (62%) say that they worry their children might be bullied at some point, compared with about half (49%) of those whose youngest child is a teenager. Similarly, about six-in-ten (57%) parents with children younger than 6 worry that their children might be kidnapped, compared with 50% of those whose youngest child is between 6 and 12 years old, and even fewer among those with only teenagers (38%).

At what age should children be left alone without adult supervision?

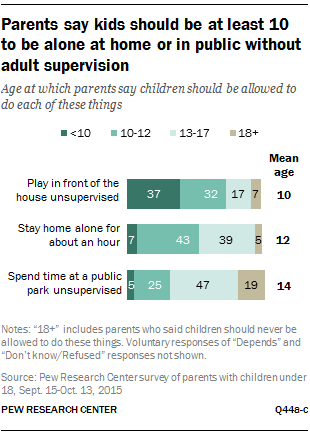

While some states and jurisdictions have laws or guidelines about when children can or should be allowed to be at home or in public without adult supervision, the decision often rests with parents, and half or more say kids should be at least 10 years old before they are allowed to play in front of the house, stay home alone for a short period, or spend time at a public park unsupervised.

While some states and jurisdictions have laws or guidelines about when children can or should be allowed to be at home or in public without adult supervision, the decision often rests with parents, and half or more say kids should be at least 10 years old before they are allowed to play in front of the house, stay home alone for a short period, or spend time at a public park unsupervised.

The average age at which parents say children should be allowed to play in front of the house unsupervised while an adult is inside is 10. On average, parents say children should be older than that before they are allowed to stay home alone for about an hour (12 years old) or to spend time at a public park unsupervised (14 years old).

Parents’ notions about when it is OK for children to be unsupervised at home and in public are correlated with their views of their neighborhood as a good place to raise kids. For example, among parents who describe their neighborhood as excellent or very good, the average age at which a child should be allowed to play in front of the house unsupervised is 9, compared with 11 for those who describe their neighborhood as fair or poor. Similarly, those who give their neighborhood high marks say a child should be 13 years old in order to spend time at a public park unsupervised; those who say their neighborhood is a fair or poor place to raise kids say children should be at least 15 to be at a public park unsupervised.

On two of the three items, Hispanic parents give a higher age, on average, than do white or black parents. For example, the average age at which Hispanic parents say children should be allowed to spend time at a public park unsupervised is 15, compared with 13 among white parents and 14 among black parents. Similarly, Hispanic parents think children should be 14 before they can stay home alone for about an hour, while white parents say this should be allowed to happen when children are 12 and black parents say it should happen when children are 13. When it comes to letting kids play in front of the house while an adult is inside, white parents give a considerably lower age (9 years old) than do black or Hispanic parents (12 years old each).

Divorced and separated parents more likely to disagree about raising kids

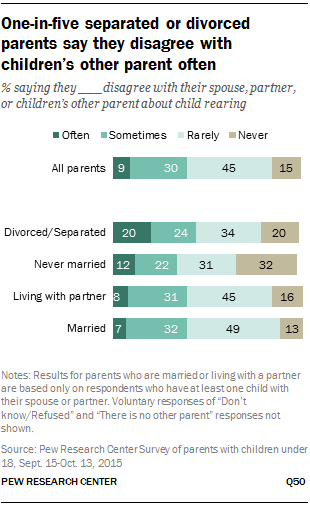

While mothers and fathers approach parenting differently in many respects, from the way they describe themselves as parents to the concerns they have, relatively few say they often have disagreements with their spouse, partner, or children’s other parent about how to raise the kids.

While mothers and fathers approach parenting differently in many respects, from the way they describe themselves as parents to the concerns they have, relatively few say they often have disagreements with their spouse, partner, or children’s other parent about how to raise the kids.

Overall, about one-in-ten (9%) say this is the case; an additional 30% say they sometimes have disagreements, while most say they rarely (45%) or never (15%) do.

Parents who are divorced or separated are more likely than other parents to say they often have disagreements about child rearing with the other parent of their child or children. One-in-five divorced or separated parents say this is the case, compared with 12% of parents who have never been married and are not cohabiting, 8% of those who are living with a partner with whom they share at least one child, and 7% of those who are married to the parent of one or more of their children.

But divorced or separated parents are also among the most likely to say they never have disagreements with their children’s other parent. One-in-five say this, compared with 16% of cohabiting and 13% of married parents. Single parents who have never been married are the most likely to say they never have disagreements with their children’s other parent about how to raise the kids; 32% say this.

-

-